Historical Facts & Fiction

Blog categories

📡 The Courage to Transmit – Danger in Salbris

By late April 1944, Muriel Byck — now operating under the field name Violette — had settled into the small town of Salbris. There, she was housed by Antoine Vincent, a local garage owner and long-standing Résistance contact. His garage — unremarkable, open to the public, and frequented by German soldiers — was the perfect cover. And it was also incredibly dangerous.

This was her reality: staying invisible in plain sight.

Behind an unassuming garage facade, a young woman defied an empire.

By late April 1944, Muriel Byck — now operating under the field name Violette, and sending messages to London under the codename Benefactress — had settled into her first real SOE base: the small town of Salbris, in the Loir-et-Cher.

There, she was housed by Antoine Vincent, a local garage owner and long-standing Résistance contact. His garage — unremarkable, open to the public, and frequented by German soldiers — was the perfect cover. And it was also incredibly dangerous.

Muriel established four radio transmitting sites, rotating between them by bicycle. One of those transmitters was hidden in a shed behind Vincent’s garage — only meters from where German troops came daily to have their bicycles repaired.

This was her reality: staying invisible in plain sight.

🧳 Arrival in Salbris

Muriel arrived with her organiser, Baron Philippe de Vomécourt — codename Antoine — who took a personal, almost paternal interest in her safety. On her first day, they lunched in a local restaurant — only for Muriel to discover it was packed with German soldiers.

The point, Vincent later explained, was to prepare her. To teach her how to function under pressure. To learn to breathe through danger.

Muriel didn’t flinch. Not even when it counted most. But the meal didn’t taste very well.

📸 Above: Vincent’s garage in Salbris, photographed after the war, now under a different name. A humble place that hid tremendous courage. Photo - Michel Septseault via Tony Lark

👁️ The Day She Was Seen

One day, while transmitting from the shed, Muriel looked up — and froze. An eye was watching her through a knothole in the wooden wall.

A German soldier.

She was mid-transmission. But instinct kicked in. She sent a danger signal, signed off, and packed up her set. The guard meant to be posted outside had vanished. There was no protection.

Muriel left no trace behind. She quietly returned to the main garage, where Vincent was elbow-deep in a gearbox. He read her face instantly.

Within minutes, he had called de Vomécourt, who arrived in his Citroën and spirited her away.

Hours later, 40 to 50 German soldiers arrived to raid the garage.

They found nothing. The soldier who’d spotted her was humiliated and punished.

Muriel’s composure — and the Resistance’s quick coordination — had saved her life.

📖 From The Call of Destiny

She was halfway through encoding the coordinates when she felt it — a shift, a stillness. Not a sound. A presence. There — on the opposite wall — a crack in the wood where a sliver of light shone through. And within it: an eye.

Perfectly framed in a knot-hole of warped timber.

It blinked once. Then vanished…

🧠 Intelligence in Motion

Muriel continued her work, cycling between alternate locations and transmitting under tight precautions. The Vincent family adored her. To them, she was more than a guest — she was one of their own.

To the SOE, she was a vital link to London.

To the Germans, she remained a ghost. Almost caught, but never quite found.

📸 Above: Antoine Vincent and his Résistance group in Salbris. Photo - De Vomécourt collection

💭 Reflection

The incident in Salbris — when Muriel was nearly discovered — is the best-known episode in the short, intense life of this otherwise little-known SOE agent.

It was a combination of swift judgment, good luck, and the tightly run Resistance network around her. But it was also a testament to her courage — and to the deep, almost psychic connection her organiser, de Vomécourt, had with her wellbeing. I’ve come across no other organiser so invested in his wireless operator’s safety, and so utterly devastated when she later died in his arms in th hospital.

Muriel’s meticulous actions in the shed — sweeping, covering her tracks, walking instead of running — speak volumes. By 1944, wireless operators in France had a life expectancy of less than six weeks. She knew the odds. She knew what had happened to the others.

Her sangfroid is astonishing. It’s one of the clearest reasons why she truly was cut out to be an SOE agent in occupied France. That day in Salbris, she earned her stripes.

The Call of Destiny

Codename Violette

Timeless Spies is both a literary endeavor and a passion project, dedicated to immortalizing the legacy of the 40 female secret agents of the SOE in France during WWII.

Release date 15 July 2025🗓 Next Week

➡️ The Final Message – Illness, Collapse, and Legacy

📖 The Call of Destiny: Codename Violette launches 15 July.

📬 Subscribe to follow Muriel’s full journey.

Note: This article draws on the work of SOE historian Paul McCue (HS9/1539/5 de V file), used with permission.

🪂 The Parachute Drop – First Steps in Occupied France

On Easter Sunday 1944, a young woman stepped into the dark above France… and into history.

By April 1944, Muriel Byck was just 25 years old — but had already survived SOE training, fallen in love, and committed to a mission that would take her deep into Nazi-occupied France. Though she hadn’t completed her final training phase, the need for wireless operators was too urgent. D-Day was imminent, and the flurry of messages flying back and forth over the English Channel grew by the day. Muriel agreed to go.

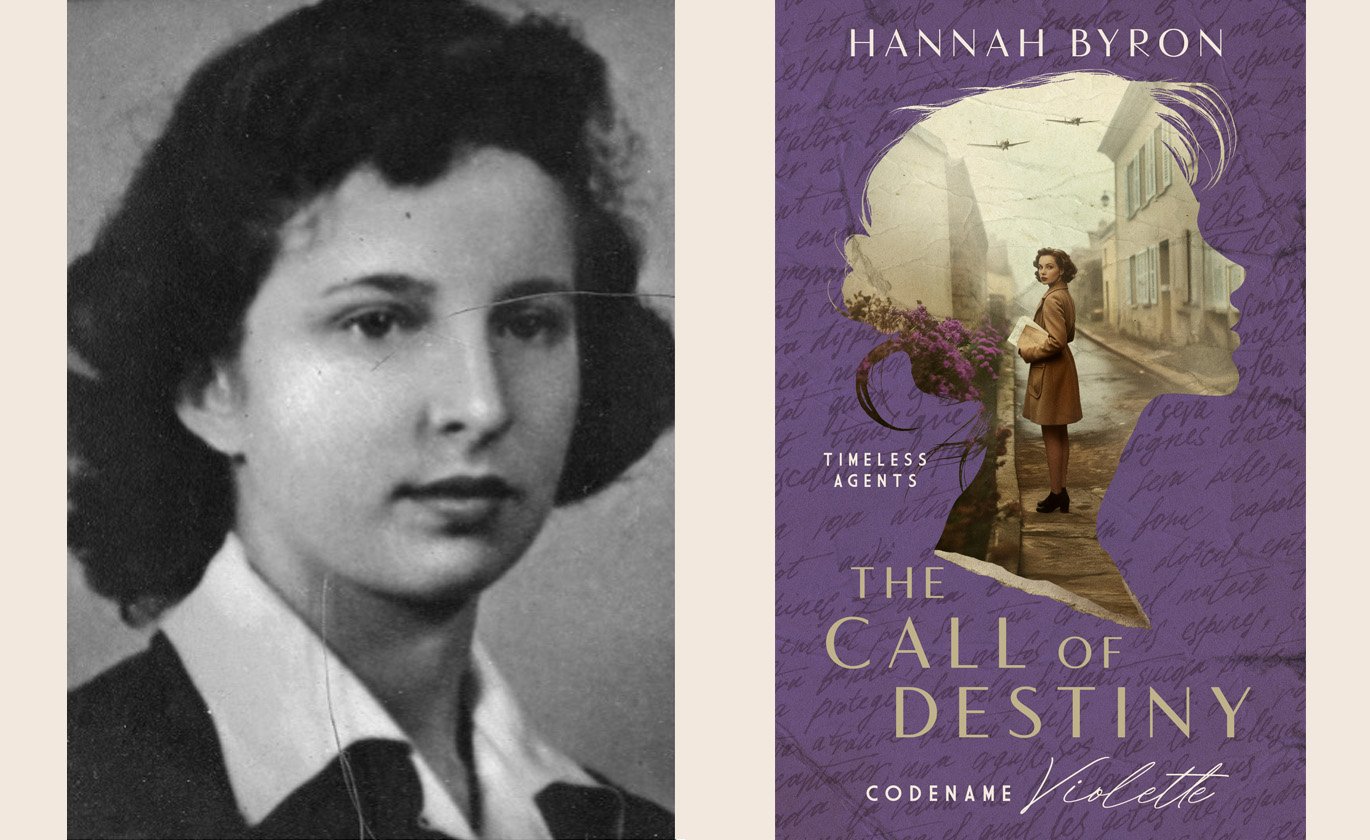

Though of poor quality, these photographs are from a false ID card issued to Muriel in France. Photo – via Tony Lark.

On Easter Sunday 1944, a young woman stepped into the dark above France… and into history.

By April 1944, Muriel Byck was just 25 years old — but had already survived SOE training, fallen in love, and committed to a mission that would take her deep into Nazi-occupied France. Though she hadn’t completed her final training phase, the need for wireless operators was too urgent. D-Day was imminent, and the flurry of messages flying back and forth over the English Channel grew by the day. Muriel agreed to go.

Her cover identity: Michèle Bernier, a governess from Paris.

Her field name: Violette.

Her assignment: to support veteran agent and organiser of the VENTRILOQUIST Network, Philippe de Vomécourt, in the Loir-et-Cher area.

🌒 Easter Sunday at Tempsford

Muriel’s departure was delayed by bad weather for two nights. On the third — Easter Sunday, 9 April 1944 — she finally boarded a Hudson aircraft with Major Sydney Hudson and Captain George Jones.

The plan had been for them to land at a Resistance-organized drop zone near Issoudun. But due to scheduling conflicts, the drop had to be blind — no reception party, no welcoming faces, no margin for error.

Muriel jumped into a forest in central France, in the pitch of night.

🌲 Landing in the Dark

The descent went smoothly, but the drop site — a wooded area instead of a clearing — added instant risk. Miraculously, Muriel’s parachute didn’t snag in the trees. She regrouped with Hudson and Jones, and the three worked by lamplight to retrieve their scattered supply containers, including Muriel’s wireless set.

As dawn broke, they left the trees and walked into the unknown.

By 8 a.m., they reached the town of Issoudun. Muriel and Jones stayed in a café while Hudson made contact with local ally Jacques Trommelschlager — the first link in the hidden network that would sustain them.

Muriel, now Michèle, was officially behind enemy lines.

🏡 Shelter in Chédigny

A few days later, Muriel was driven — via backroads and Resistance contacts — to a safe house in the village of Chédigny, in the Indre-et-Loire. There, she stayed with Madame Marthe Dauprat-Sevenet, the mother of another SOE agent, Captain Henri Sevenet.

Despite exhaustion from the journey and an early episode of illness en route, Muriel began to recover in this quiet, flower-filled village. She helped around the house, charmed her host, and won the trust of the household. Madame Sevenet later described her as “full of charm, full of courage, full of life.”

To outsiders, she was simply a young woman, resting in the countryside.

To the Resistance, she was Violette, preparing to transmit Allied intelligence from the heart of occupied France.

Le Breuil, the house of Madame Marthe Dauprat-Sevenet in Chédigny, where Muriel first stayed in France. Photo – Paul McCue’s collection.

📖 Snippet From The Call of Destiny

Whatever it was—exhaustion from the three tense nights, or Heaven granting her a small mercy—Muriel closed her eyes before takeoff and, somehow, slept. Soundly. Deeply. Until a hand shook her shoulder.

“Violette! We’re almost there.”

The engines roared in her ears. The smell of oil and metal filled her nose. She blinked. Outside the tiny window: darkness—and then, the glow of the full moon. A smattering of stars. France.

The signal light turned green. Albin slid down the chute first. She followed, as if in a dream. Isidore came last. The wind tore the thoughts from her head. And then—silence.

A bloom of white above her. The eerie hush of descent. A world stilled under moonlight. Three parachutes. Three agents. She wasn’t alone.

Below: France.

She hit the ground hard. Rolled. Coughed once. Lay still, her heart pounding, waiting for the signal. Footsteps. She held her breath.

Then—Albin appeared, grinning like a wolf. “You made it.”

“I did.” Her voice trembled, then steadied. “Where’s Isidore?”

“Safe. Bloody trees. Bit of a miracle we didn’t all end up dangling in one.”

“True.”

There was no time to reflect. Just movement. The three of them stripped off their harnesses and jumpsuits. Buried their parachutes in silence. Found their sets. One by one, they shrugged on civilian jackets and French identities.

What remained were three British agents—French in name only—armed with false papers and a trembling kind of hope.

🔐 Layers of Cover

Muriel’s cover was carefully constructed. She was to be passed off as the fiancée of Henri Sevenet. Her forged papers, her new name, her memorized background — everything had to hold up under German scrutiny. Any slip could mean arrest, torture, or worse.

Yet even amid danger, she never lost her warmth. She made tea, she listened, she joked with those around her. One small detail stands out: she insisted on taking Maurice Martin’s powder compact into the field — aged with ammonia to look worn. A tiny token of love, carried through the fire.

💭 Reflection

While writing Muriel’s story and “living” with her for the months I did, she came to life for me as an extraordinary mix: quiet and self-possessed on the outside, fearless and determined on the inside.

Her sudden, deep-felt love affair with fellow agent Maurice Martin is somewhat of an enigma to me. Perhaps it was the intensity of being thrown together in the unfamiliar Scottish Highlands, training like modern-day commandos. Perhaps she needed his support. Perhaps she needed to be in love — to be engaged — in order to dare enter France knowing someone would be waiting for her when the war was over. Maybe it truly was love at first sight.

We’ll never know. It may have been all these things.

But they separated, and Muriel went to France. From the beginning, she struggled with the stress and the physical demands of constant movement under harsh conditions. The signs of illness appeared early on, yet she soldiered on.

I’m absolutely certain she would not have wanted to miss one second of the hardship and terror that filled those six weeks of her mission.

Muriel was where she belonged — fighting for the freedom of France.

📅 Next Week

➡️ Signals in the Shadows – Muriel’s First Transmissions and the Day the Enemy Saw Her🗓 The Call of Destiny: Codename Violette launches 15 July

Note: This series of blog posts—and most of the accompanying photographs—are based on SOE historian Paul McCue’s research on Section Officer Muriel Tamara Byck (HS9/1539/5 de V file). Used with permission.

💥 Becoming Violette – Muriel’s SOE Training and Love Story

Just before she left, Maurice gave Muriel a leather powder compact—a farewell token, personal and cherished. They were engaged. De Vomécourt thought it looked suspiciously new and nearly forbade her from taking it. But Muriel insisted. With a little help from ammonia to age its surface, the compact was allowed to travel with her into occupied France.

We don’t know if it went with her into her grave, or whether it was returned to England—a small, silent witness to a brief but powerful wartime love.

Bombed house in Torquay of Muriel Byck’s family (clickable)

History rarely shows us the quiet before the storm. But in this photo, taken in 1943 after a German air raid on Torquay, we glimpse a moment of devastation that changed one woman’s path forever. The man standing amid the rubble is George Leslie, Muriel Byck’s stepfather. The house behind him was theirs. It was a wonder the family survived. Elsewhere in Torquay that day, dozens of Sunday school children and their teachers weren’t as lucky.

The walls that crumbled around Muriel may have shattered more than bricks.

Just a month later, she made a decision that would lead her deep into the shadows of occupied France: she volunteered for the Special Operations Executive as a secret agent—fully aware of the danger that awaited her.

This blog post traces the beginning of that journey—from a battered home in Devon to the secret training grounds of the SOE—and the unexpected love that blossomed along the way. Before she became “Violette,” Muriel was a young woman caught between duty, heartbreak over her parents’ divorce, and an unshakable desire to do more. Despite her delicate health and quiet nature, she pressed forward.

📝 First Impressions

Muriel’s initial assessment at SOE’s Winterfold screening center paints the picture of a young woman who stood out not through bravado, but through character:

“A quiet, bright, attractive girl, keen, enthusiastic and intelligent… She is self-possessed and persistent, and warm in her feeling for others.”

The examiners noted she lacked guile and foresight—qualities prized in undercover work—and would need extensive training. But they also saw potential. Enough, at least, to send her forward.

Muriel was selected for Group A training—paramilitary basics—and dispatched to one of SOE’s most remote centers: Meoble Lodge, in the Scottish Highlands.

🏔️ Meoble Lodge: Rain, Rifles, and Revelation

At Meoble, Muriel endured grueling hikes, weapons handling, and survival exercises in freezing rain. Though never physically robust, she kept pace, earning the admiration of her instructors. Lieutenant Oliver, her conducting officer, wrote of her charm, strength of character, and surprising depth.

But Oliver’s admiration remained one-sided.

It was there, in the remote wilds of Scotland, that Muriel quietly fell in love—not with the landscape, but with Second Lieutenant Maurice Martin, a French OSS trainee operating under the alias Maurice Morange. A fellow outsider. A kindred spirit. I’ve come to think of them as le couple français.

Together, they learned to decode, to disarm, to disappear.

Their connection grew not from stolen moments, but from shared silences—glances in the mess hall, trust forged under tension. In the middle of war, they found something tender—and real.

📡 Promise and Pressure

By the end of training, Muriel had proven herself exceptionally capable in Morse and technical skills, but physically fragile. She was given a rare double grading: C (fit to serve with conditions) and F (fail).

And yet, such was the urgency of the moment that she was moved forward—first to Thame Park for W/T (wireless transmission) training, then parachute training at Ringway. Maurice remained close by her side. They were inseparable.

Philippe de Vomécourt

Muriel’s final phase of training—the vital “Finishing School” at Beaulieu—was waived. SOE needed a wireless operator immediately. Philippe de Vomécourt, one of SOE’s most experienced agents, was preparing to return to France.

Muriel was offered the assignment. She accepted.

Her codename in London: BENEFACTRESS

Her name in the field: Violette

Her false identity: Michèle Bernier, a governess from Paris

💌 A Final Gift

Just before she left, Maurice gave Muriel a leather powder compact—a farewell token, personal and cherished. They were engaged. De Vomécourt thought it looked suspiciously new and nearly forbade her from taking it. But Muriel insisted. With a little help from ammonia to age its surface, the compact was allowed to travel with her into occupied France.

We don’t know if it went with her into her grave, or whether it was returned to England—a small, silent witness to a brief but powerful wartime love.

📖 From The Call of Destiny

Outside, the lamps of London flickered against war-darkened skies. Inside Le Régent, two lovers held on to a moment suspended in time—before the occupied land of their beloved France would call them home.

Later that night, as they walked back through the blackout streets, they said little. There was no need. They’d said it all. At the door of the apartment SOE had rented for Muriel, he tucked a curl behind her ear and kissed her again.

“Reviens vers moi,” he repeated.

“I will,” she whispered. “And you, Maurice Martin… you’d better come back to me as well.”

They didn’t know then that it would be their last kiss. But perhaps some part of them did.

Muriel Byck in uniform

💭 Reflection – How I see Muriel in this stage

Muriel’s path to becoming Violette must have been gruesome for the well-educated, soft, lovely girl she really was. But Muriel had one trait that overshadows all fallibility: she had an iron will. She bit off more than she could chew. Maybe she knew that. Maybe she didn’t. But she was prepared to die for France. To die for freedom.

I believe that drive is what carried her through the grueling training. Her strength wasn’t the kind that screamed. It was the kind that endured.

And through it all, she carried with her a quiet love—not a distraction from duty, but a reason to be brave. How she must have welcomed Maurice’s warmth in those icy months, knowing full well that they would be parachuted into France separately, and the chances of seeing each other again were heartbreakingly slim.

📅 Next Week

➡️ Into the Shadows – Muriel’s Parachute Drop and Arrival in Occupied France

🗓 The Call of Destiny: Codename Violette launches 15 July

📬 Subscribe to follow the rest of Muriel’s extraordinary journey.

Note: This series of blog posts—and most of the accompanying photographs—are based on SOE historian Paul McCue’s research on Section Officer Muriel Tamara Byck (HS9/1539/5 de V file). Used with permission.

June's Fire: Honoring the SOE Women Born This Month

June’s daughters of the SOE remind us of the breadth—and the cost—of courage. Muriel Byck, Pearl Witherington and Violette Szabo. Each of them carved a legacy in their own way: through loyalty, leadership, or the ultimate sacrifice. Their stories remind us that resistance is not a single act, but a way of living—even when the odds are against you.

As a fellow June girl, I carry a quiet connection to these women. And each year, as their birthdays return, I’m reminded that history doesn’t rest—it waits to be remembered.

June brings us three extraordinary women from the Special Operations Executive’s Section F—each of them fierce, resilient, and unforgettable. Muriel Byck, Pearl Witherington, and Violette Szabo didn’t just support the Resistance—they were the Resistance. Their courage, loyalty, and sheer determination lit fires behind enemy lines and left legacies that still burn bright today.

And June feels especially close to my heart—because it’s also the month I was born. Every time I write these tributes, I feel a deep connection to the women I honor, but this month, perhaps even more so. These three agents, in their unique ways, reflect so much of what I admire: compassion, clarity of purpose, and bold, quiet power.

In this month’s trio, we find a fragile wireless operator whose spirit never faltered, a battle-tested leader who defied male hierarchy, and a young widow-turned-heroine whose courage became legend. Two did not live to see the peace they fought for. One demanded to be remembered not just as a woman spy—but as a commanding officer.

Each of these women features—or will feature—in my Timeless Agents series. But here, as always, we strip the fiction away and let their real stories shine.

Muriel Byck – Codename Violette

Muriel Byck’s life was marked by quiet strength and deep conviction. Born in London in 1918 to Russian Jewish émigré parents, she spoke fluent French and had a passion for service that led her first to the WAAF and eventually to the SOE. Trained as a wireless operator—a role with one of the shortest survival rates—Muriel was deployed to France in April 1944, just weeks before D-Day. Her cover identity, Michèle Bernier, was a governess from Paris. Her real task: transmitting coded messages in support of the VENTRILOQUIST circuit.

Despite struggling with poor health, she carried out her mission with unwavering dedication until she suddenly collapsed with meningitis. She died on 23 May 1944, just days before her 26th birthday. Her fellow agent, the hardened resistance leader Philippe de Vomécourt wept at her funeral.

Muriel’s grave first lay in the town of Romorantin, later she was reinterred at the Military Cemetery in Pornic, France. Her story features in The Call of Destiny, my third book in my Timeless Agents series—a tribute to the power of courage that burns quietly, but brightly.

Pearl Witherington – Codenames Marie / Pauline

Few SOE agents fought harder—not just in the field, but for recognition—than Pearl Witherington. Born in Paris to British parents, Pearl grew up fluent in French and fiercely independent. When the Germans invaded France, she fled to Britain and joined the SOE, determined to return and fight. Parachuted into central France in 1943, she initially worked as a courier but quickly rose to lead the Wrestler circuit after her superior was arrested. Under her command, more than 1,500 Resistance fighters sabotaged German rail lines, blew up supply depots, and disrupted troop movements during the lead-up to D-Day.

Despite her achievements, Pearl was initially offered only a civilian MBE. She returned it in protest, stating that she had been a soldier—and should be recognized as such. Years later, she was finally awarded the military MBE and honored as a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur in France. After the war, she settled in the Loire Valley with her SOE radio operator and husband Henri Cornioley.

Pearl’s story is a sharp reminder that women were not only vital to the Resistance—but also often overlooked. She didn’t accept that. And thanks to her refusal to stay silent, neither do we.

Violette Szabo – Codename Louise

If there is one name from the SOE that echoes like poetry and thunder, it’s Violette Szabo. Born in Paris to a French mother and British father, Violette was widowed at 22 when her French Foreign Legion husband was killed in North Africa. Grieving but resolute, she volunteered for the SOE, determined to fight back. She was parachuted into France twice, serving as a courier and saboteur with fearless resolve.

On her second mission in June 1944, Violette was captured after an intense gun battle near Salon-la-Tour. Despite brutal interrogation and torture, she never revealed her secrets. Deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp, she continued to show solidarity, compassion, and bravery until her execution in February 1945 at the age of 23.

Posthumously awarded the George Cross, Croix de Guerre, and Médaille de la Résistance, Violette became a symbol of resistance, sacrifice, and unwavering spirit. Her life inspired poems, books, and a 1958 film—but perhaps most moving of all is the small museum dedicated to her in Herefordshire, created by her devoted aunt.

Conclusion: June’s Legacy of Light and Fire

June’s daughters of the SOE remind us of the breadth—and the cost—of courage. Muriel Byck, whose frail body belied her strength of will. Pearl Witherington, who led Resistance fighters through sabotage and strategy with military precision. And Violette Szabo, who died without betraying her comrades and with her dignity unbroken.

Each of them carved a legacy in their own way: through loyalty, leadership, or the ultimate sacrifice. Their stories remind us that resistance is not a single act, but a way of living—even when the odds are against you.

As a fellow June girl, I carry a quiet connection to these women. And each year, as their birthdays return, I’m reminded that history doesn’t rest—it waits to be remembered.

A Voice Across Borders – Muriel Byck’s Unlikely Path to War Heroine

When I first discovered Muriel Byck’s story, I was struck not just by her bravery—and her tragic six-week mission as an SOE agent in occupied France—but also by her cosmopolitan, Jewish beginnings: a rich mix of languages, cultures, and a youth spent across Europe.

Before this well-educated, quiet young woman became the fearless wireless operator codenamed Violette, she had already crossed many borders.

Introduction

When I first discovered Muriel Byck’s story, I was struck not just by her bravery—and her tragic six-week mission as an SOE agent in occupied France—but also by her cosmopolitan, Jewish beginnings: a rich mix of languages, cultures, and a youth spent across Europe.

Before this well-educated, quiet young woman became the fearless wireless operator codenamed Violette, she had already crossed many borders. She spoke perfect French, loved the theatre, and carried a deep empathy that defied the turbulent world around her.

Background

Muriel Tamara Byck was born in 1918 in west London, the daughter of Jewish refugees originally from what is now Ukraine. Her early life was anything but ordinary. As a child, she lived in Wiesbaden, Germany, and later spent four formative years in France, attending the Lycée de Jeunes Filles in Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

When the family returned to England, Muriel continued her French education at the Lycée Français in South Kensington, where she passed her Baccalauréat in 1935 — a distinction then reserved for only privileged British girls.

Muriel was fluent in French and Russian and spoke English without a trace of an accent. At eighteen, she seemed destined for an academic or artistic path. She pursued further studies at the Université de Lille and, upon returning to London, worked first as a secretary and then in theatre, including a stint as assistant stage manager at the Gate Theatre in Charing Cross. Stage management became her world — lights, scripts, cues — until the war called her elsewhere.

Like many young women of her generation, Muriel’s life changed dramatically with the outbreak of WWII. She joined the Women’s Voluntary Service and later worked with the Children’s Overseas Reception Board, helping evacuate children away from the Blitz. She also served as an ARP warden and a Red Cross librarian — all before enlisting in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) in 1942.

But it wasn’t enough. Perhaps it was the air raid that damaged her mother’s home in Torquay in 1943, or perhaps it was always in her nature — Muriel volunteered for SOE and stepped into the annals of history.

Quote from the Source

“A quiet, bright, attractive girl, keen, enthusiastic and intelligent… warm in her feeling for others.” — SOE assessment, 1943

Snippet from The Call of Destiny

She had known. She had seen it coming. And yet—some part of her had still hoped. Hoped that war might be avoided. War was definitive. War was black and white. No one could hide in neutrality anymore.

And that included her.

Closing Reflection

Muriel’s early life reminds us that resistance often begins not with weapons, but with empathy, education, and an unshakable sense of purpose.

In the weeks to come, I’ll be sharing more about Muriel’s life and her courageous mission behind enemy lines — and how her legacy inspired my upcoming novel, The Call of Destiny: Codename Violette.

How I, as an author, see Muriel

“I think of her — the girl with a quiet voice, a coy smile, and an iron will. She crossed mental and physical borders long before she parachuted into France in 1944 to become de Vomécourt’s W/T operator in the Sologne.”

✨ The Call of Destiny launches on 15 July 2025. Stay tuned for next week’s post: “Becoming Violette – Muriel’s SOE Training and Love Story.”

🔗 Preorder here mybook.to/CallOfDestiny

Note: This series of blog posts—and most of the accompanying photographs—are based on SOE historian Paul McCue’s research on Section Officer Muriel Tamara Byck (HS9/1539/5 de V file). Used with permission.

May’s Silent Warriors: Honoring the SOE Women Born This Month

As the month of May unfolds, we turn the page on another chapter of remembrance—this time for the five brave women of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), Section F, who were born during this spring month.

Among all the months we honor, May stands apart for a rare and remarkable reason. May’s daughters remind us that courage sometimes means not only fighting, but surviving when the guns fell silent.

As the month of May unfolds, we turn the page on another chapter of remembrance—this time for the five brave women of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), Section F, who were born during this spring month.

From Christine Granville, the legendary Polish countess with nerves of steel, to Francine Agazarian, the radio operator who vanished back into everyday life, these women carried secrets, messages, and hope across enemy lines. All of them left an imprint on the war—and on history—that must never be erased.

May’s list brings together not only familiar names like Lise de Baissac, who parachuted into France as part of the earliest SOE landings, but also quieter heroines like Sonya Butt and Blanche Charlet, whose courage played out in quiet fields, coded messages, and midnight missions.

As with every monthly tribute, these posts are part of my effort to spotlight the women who inspire my Timeless Agents series—fiction rooted in real-life bravery. Through this blog, and across my social media, I hope to keep their memory vivid and enduring.

You can explore more about each woman through the links below each post, and I invite you to join me in honoring May’s Silent Warriors.

Christine Granville – Codename Pauline

Known as one of the most daring women to serve in the SOE, Christine Granville—born Krystyna Skarbek—was a Polish aristocrat who became Britain’s first and longest-serving female spy during WWII. Fluent in multiple languages and fearless in the field, Christine served in Poland, Hungary, North Africa, and France, showing extraordinary resourcefulness and resolve.

Her charm and cunning saved lives, including her own, as she bluffed her way past Gestapo officers and bribed her way into prisons to free captured comrades. She once skied across the Tatra Mountains in winter to deliver intelligence and, in another mission, reportedly pulled a knife on a Nazi officer.

Christine was described by one fellow agent as “a flaming sword of freedom”—a woman of instinct, grit, and sheer will. Tragically, she survived the war only to be murdered in London in 1952. Her legacy is immense, and her story is still told as one of the most compelling in the SOE’s history.

Francine Agazarian – Codename Marguerite

Francine Agazarian, born Françoise Isabella, was one of the many quietly heroic figures of the SOE. She served as a courier for the PROSPER network, working alongside her husband André Agazarian, who was a wireless operator. Together, they took enormous risks, delivering messages, coordinating arms drops, and maintaining vital communication lines for the Resistance in and around Paris.

In 1943, as German counter-intelligence closed in, Francine was recalled to London for her safety. Tragically, André was arrested shortly afterward and executed at Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1944.

The war left Francine a widow, and though she survived, her life was forever marked by the immense losses she endured, as she was the only one of her network to survive. Francine rarely spoke publicly about her experiences, quietly carrying the weight of memory.

She was later awarded the Croix de Guerre and the King’s Medal for Courage in the Cause of Freedom for her bravery. Her story stands as a reminder that even among the survivors, the scars of war ran deep.

Lise de Baissac – Codename Odile

Few SOE agents embodied quiet determination like Lise de Baissac. Born into a French-Mauritian family, Lise was among the first women to parachute into occupied France in September 1942—an extraordinary feat for the time.

Operating under the codename Odile, and later Marguerite, she established safe houses, gathered intelligence, and coordinated Resistance activities around Poitiers, often cycling dozens of miles under the enemy’s nose. Known for her sangfroid, Lise approached each mission with steely calm and meticulous preparation.

During her second mission she joind her brother’s network SCIENTIST network work that supported the D-Day landings and helped destabilize German communication lines.

After the war, she was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the MBE, yet remained strikingly humble about her wartime contributions. Lise’s life and spirit inspired my novel The Color of Courage: Codename Odile, where I had the privilege of bringing her extraordinary story to a new generation of readers.

Sonya Butt – Codename Blanche

At just 20 years old, Sonya Butt became one of the youngest female agents to serve with the SOE. Trained as a courier and wireless operator, she parachuted into occupied France in 1944, working with extraordinary courage to maintain communications between Resistance groups and London.

Despite the immense dangers—constant surveillance, the threat of betrayal, and brutal punishment if captured—Sonya moved through her missions with resilience and quiet bravery.

After the liberation of France, Sonya did what few of the other female agents managed: she built a joyful, lasting life. She married fellow SOE agent Guy d’Artois, moved to Canada, and together they raised six children.

Her post-war life was filled with the very things so many fought to protect: family, freedom, and peace. Sonya’s story stands as a testament to hope and new beginnings after unimaginable risk.

Blanche Charlet – Codename Christiane

Before the war, Blanche Charlet lived a vibrant life as an art dealer, running a gallery specializing in modern art in Brussels. But when Germany invaded Belgium in 1940, Blanche fled to Britain—only to return to danger voluntarily. Recruited by the SOE, she parachuted into occupied France in August 1942 under the codename Christiane. As a courier for the VENTRILOQUIST network, she transported vital intelligence under constant threat. Captured by the Germans, she endured harsh imprisonment but staged a daring escape in November 1942, making her way across France before returning to England via Brittany in April 1944.

Awarded the MBE for her bravery, Blanche lived the remainder of her life more quietly, a survivor of extraordinary times. Her journey from art galleries to underground resistance operations is a testament to how courage can bloom from the most unexpected places.

Conclusion: May’s Survivors

Among all the months we honor, May stands apart for a rare and remarkable reason: every single SOE woman born this month survived the war. Christine Granville, Francine Agazarian, Lise de Baissac, Sonya Butt, and Blanche Charlet—all faced imprisonment, betrayal, near capture, and unimaginable danger. And yet, through adaptability, endurance, and sheer will, they returned.

Their lives after the war took many forms—quiet anonymity, joyful family life, continuing service—but their survival itself stands as a defiant victory. May’s daughters remind us that courage sometimes means not only fighting, but surviving when the guns fell silent.

April's Daughters: Honoring the SOE Women Born This Month

April is the most remarkable month in our calendar of remembrance, with eight female agents of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), Section F born during this time. These women came from all walks of life and across continents, united by a singular mission: to serve behind enemy lines in France and resist Nazi occupation during WWII.

Their courage echoes through time. Some survived the war and returned to quiet lives. Others paid the ultimate price, executed in camps or lost in the field. Some left behind photographs and medals. Others left behind only a name and codename—but all left their mark on history.

April is the most remarkable month in our calendar of remembrance, with eight female agents of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), Section F born during this time. These women came from all walks of life and across continents, united by a singular mission: to serve behind enemy lines in France and resist Nazi occupation during WWII.

Their courage echoes through time. Some survived the war and returned to quiet lives. Others paid the ultimate price, executed in camps or lost in the field. Some left behind photographs and medals. Others left behind only a name and codename—but all left their mark on history.

This monthly tribute is part of my broader effort to honor these women through the Timeless Agents series—historical novels that blend dual timelines to preserve their legacy for a new generation. But this space is just for them. A quiet corner to remember their birthdays, their bravery, and their stories.

April has the highest number of SOE birthdays, followed closely by January with seven agents. Let us now turn to these eight extraordinary women—April’s daughters—who dared to stand in the shadows and fight for freedom.

1. Virginia Hall Or The Limping Lady Who Terrified the Gestapo

Few agents in the Second World War struck as much fear into the Gestapo as Virginia Hall. Known to them as “the most dangerous of all Allied spies,” she was—remarkably—an American woman with a wooden leg. That didn’t stop her from serving first with the British SOE and later with the American OSS, coordinating resistance networks, organizing sabotage, and guiding escaped prisoners over the Pyrenees.

Nicknamed "La Dame qui Boîte", or "The Limping Lady," Virginia’s prosthetic leg, which she nicknamed “Cuthbert,” became legendary in its own right. After being rejected by the U.S. Foreign Service due to her disability, she found her calling in the shadows—serving fearlessly behind enemy lines.

Virginia Hall’s story is one of sheer defiance. She operated in Vichy France under constant threat of capture, often disguising herself as a peasant woman and filing her teeth to appear older. Even after being forced to flee over the mountains into Spain, she returned to occupied France in 1944 to assist the Resistance ahead of the D-Day landings.

For her service, she was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the Croix de Guerre, and made a Member of the Order of the British Empire—the only civilian woman to receive the DSC during WWII.

Her legacy continues to inspire generations of intelligence officers, and her story is now widely taught and celebrated, including by the CIA, where she later worked. You can read more about Virginia Hall’s extraordinary life in this article by the CIA:

👉 Virginia Hall: The Courage and Daring of the Limping Lady

2. Phyllis “Pippa” Latour – The Last Agent Standing

In October 2023, the world lost the last surviving female agent of SOE’s Section F—Phyllis “Pippa” Latour. Born in South Africa, raised in French-speaking environments, and trained for some of the most perilous missions behind enemy lines, Pippa lived to the remarkable age of 102. Her story, like so many of her comrades, remained largely unknown for decades.

Phyllis joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) before being recruited into the SOE. At just 23 years old, she parachuted into Normandy in May 1944, working undercover as a teenage girl riding a bicycle through the French countryside. Her mission: gather intelligence and relay it to the Allies in preparation for D-Day. To protect her messages, she encrypted them in microscopic code hidden on silk, disguised as clothing repairs or hair ribbons.

Despite the enormous danger—being caught with a radio transmitter was punishable by death—she operated successfully until France’s liberation. She later said she joined to avenge the death of her godmother, who had been killed by the Nazis.

For her service, Pippa received numerous awards, including the Legion of Honour, the Croix de Guerre, and was made a Member of the Order of the British Empire.

She rarely spoke of her wartime work until much later in life, when she finally received public recognition. The BBC published a moving tribute after her passing, which you can read here:

👉 BBC: Phyllis Latour, the last female SOE agent, dies at 102

Phyllis Latour was the last link to a sisterhood of secret agents whose courage changed the course of the war. Now, she joins them in memory. The last agent has passed—but their stories live on.

For those of you who read The Color of Courage, you may remember that “Geneviève“ was the young W/T Operator who Lise de Baissac took under her wing in Normandy before and after D-Day.

3. Peggy Knight – The Leyton Typist with Nerves of Steel

Marguerite Diana Frances “Peggy” Knight may have started her career as a humble typist in Leyton, but her wartime path led her deep into the heart of Nazi-occupied France. Recruited into the SOE for her fluent French and remarkable calm under pressure, she parachuted into the Auvergne in 1944 and served as a courier for the DONKEYMAN Network.

With a bicycle, a fierce sense of duty, and nerves of steel, Peggy delivered secret messages between Resistance groups, often riding for miles under the constant threat of arrest or execution. Her courage, professionalism, and ability to maintain her cover made her an invaluable part of the underground effort to destabilize the German war machine.

Her wartime heroism earned her numerous honors, including the Croix de Guerre, US Medal of Freedom, and appointment as a Member of the Order of the British Empire.

After the war, Peggy lived a quiet life in Cornwall. Her story, like many of her comrades, was nearly lost to time—but thanks to dedicated local historians, her legacy now lives on.

You can read more about her in this article by the Leyton History Society:

👉 The Leyton Typist with Nerves of Steel

4. Marie-Thérèse Le Chêne – The Oldest Female SOE Agent

At 52, Marie-Thérèse Le Chêne became the oldest female agent sent by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) into occupied France during World War II. Serving from 31 October 1942 until 19 August 1943, she worked as a courier under the codename Adèle, operating primarily in the Lyon area alongside her husband, Henri Le Chêne, and brother-in-law, Pierre Le Chêne.

Due to her age, Marie-Thérèse did not parachute into France; instead, she arrived by boat. Her assignments involved transporting messages and coordinating with various resistance networks—a perilous role that required constant vigilance and courage.

Despite the significant risks, she successfully evaded capture and continued her operations until her extraction by the SOE on 19 August 1943. For her bravery and contributions to the resistance, she was awarded the Croix de Guerre and appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE).

Unfortunately, much of Marie-Thérèse's life after the war remains shrouded in mystery, with no known photographs or detailed records of her later years. Her story stands as a testament to the countless unsung heroes whose valor and sacrifices were instrumental in the fight against oppression.

Learn more about the Le Chêne family's involvement with the SOE here:

👉 The Le Chêne Family and the Special Operations Executive

5. Odette Wilen – The Survivor Who Disappeared into the Shadows

Odette Wilen is one of the more enigmatic SOE heroines. Born in London to a Finnish mother and a French father, she joined the war effort after the death of her husband, an RAF pilot. Trained in the SOE’s rigorous program, she was parachuted into occupied France in April 1944 to serve as a courier under the codename Sophie.

Tragically, her first contact in the field was missing—arrested days earlier in what would unravel into the betrayal of the entire PROSPER circuit, one of the SOE's largest and most successful networks. Odette found herself stranded in France, surrounded by danger and unsure whom to trust.

Amazingly, she survived. With help from sympathetic locals and extraordinary courage, she evaded capture and returned safely to England—a fate not shared by many of her comrades. After the war, she quietly left public life and eventually emigrated to Argentina, where she died in 2015 at the age of 96.

She received the Croix de Guerre, the Parachute Badge of Wings, and was made a Member of the Order of the British Empire—a testament to her bravery and resilience.

You can read more about Odette and the haunting fate of the SOE's PROSPER agents in this BBC feature:

👉 BBC: The British spies who lied, loved—and were betrayed

6. Lilian Vera Rolfe – “Beyond Courage”

Born to a French mother and British father, Lilian Vera Rolfe was raised in Paris and educated in both languages—making her a perfect candidate for the Special Operations Executive. After fleeing Nazi-occupied France, she worked in the British Ministry of Information before joining the SOE.

Parachuted into the Loiret region in April 1944 under the codename Nadine, Lilian served as a wireless operator for the HISTORIAN network. Her work was perilous: transmitting from occupied territory, constantly on the move, with the risk of capture ever-present. But she continued her missions with remarkable courage and calm.

In July 1944, her network collapsed. Lilian was captured by the Gestapo, tortured, and imprisoned in Ravensbrück concentration camp. Witnesses later recalled her bravery and kindness even in the most horrific conditions. On 5 February 1945, she was executed alongside fellow agents Denise Bloch and Violette Szabo.

Lilian was posthumously awarded the Croix de Guerre, the MBE, and was Mentioned in Despatches. She was just 30 years old.

Her story is one of steadfast spirit in the face of unimaginable cruelty—a life taken far too soon, but never forgotten.

You can read more about her in this moving profile by historian Paul McCue:

👉 Lilian Vera Rolfe: Beyond Courage – Paul McCue for ICMGLT

7. Odette Sansom – The Most Decorated Woman of WWII

Few names are as synonymous with female wartime heroism as Odette Sansom. A French mother of three living in Britain, she volunteered for SOE and was parachuted into occupied France in 1942. Operating under the codename Lise, she worked closely with fellow agent Peter Churchill, posing as his wife to mask their activities.

Odette was eventually captured, tortured at Fresnes Prison, and deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp. Despite brutal interrogations and the threat of execution, she gave nothing away—protecting her comrades and inventing the story that Churchill was related to Prime Minister Winston Churchill, a clever ploy that may have saved both their lives.

Her bravery, resistance, and sheer endurance became legendary. After the war, Odette received the George Cross—Britain’s highest civilian award for gallantry—and became the most decorated female agent of the SOE. Her honors also included the Croix de Guerre, Légion d’Honneur, and multiple British campaign and jubilee medals.

Odette’s story was dramatized in the 1950 film Odette, and she later became a prominent speaker and advocate for remembering the sacrifices of the Resistance.

You can read more about her astonishing life here:

👉 How a Housewife Became One of WWII’s Most Highly Decorated Spies – HistoryNet

8. Cicely Lefort – A Tragic End in Ravensbrück

Cicely Marie Lefort had been living a quiet life in France with her French doctor husband when the world fell into chaos. Bilingual and determined, she volunteered for the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in 1943. Trained as a courier under the codename Alice, she was sent to France to serve the JOCKEY network in southeastern regions.

Unfortunately, her mission was cut tragically short. In September 1943, Cicely was arrested by the Gestapo while carrying compromising materials. She endured torture and was eventually deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp. In February 1945, with the war nearing its end, she was executed by gas chamber.

Cicely’s story might have vanished into the silence of history, but her courage was never forgotten. She was awarded the Croix de Guerre and Mentioned in Despatches. In recent years, her American great-niece embarked on a journey to uncover her legacy—piecing together family letters, records, and resistance archives to give Cicely’s sacrifice the recognition it deserves.

Her life and death are reminders of how easily the stories of brave women can be buried—and how essential it is to bring them to light.

You can read the full article about Cicely’s rediscovery here:

👉 Moscow author pieces together puzzle of relative executed as a WWII secret agent

Honoring the March SOE Women: A Legacy of Courage

As the year progresses, I continue my tribute to the extraordinary women of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) Section F by remembering those born in March. Each of these brave agents answered the call to resist tyranny, risking their lives to support the Allied cause. This month, we honor the women whose birthdays fall in March, sharing their stories so they are never forgotten.

As the year progresses, I continue my tribute to the extraordinary women of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) Section F by remembering those born in March. Each of these brave agents answered the call to resist tyranny, risking their lives to support the Allied cause.

Through their courage, resilience, and ultimate sacrifices, they became integral to the fight against Nazi occupation in France. Their missions were perilous, their endurance remarkable, and their contributions invaluable.

This month, we honor the women whose birthdays fall in March, sharing their stories so they are never forgotten.

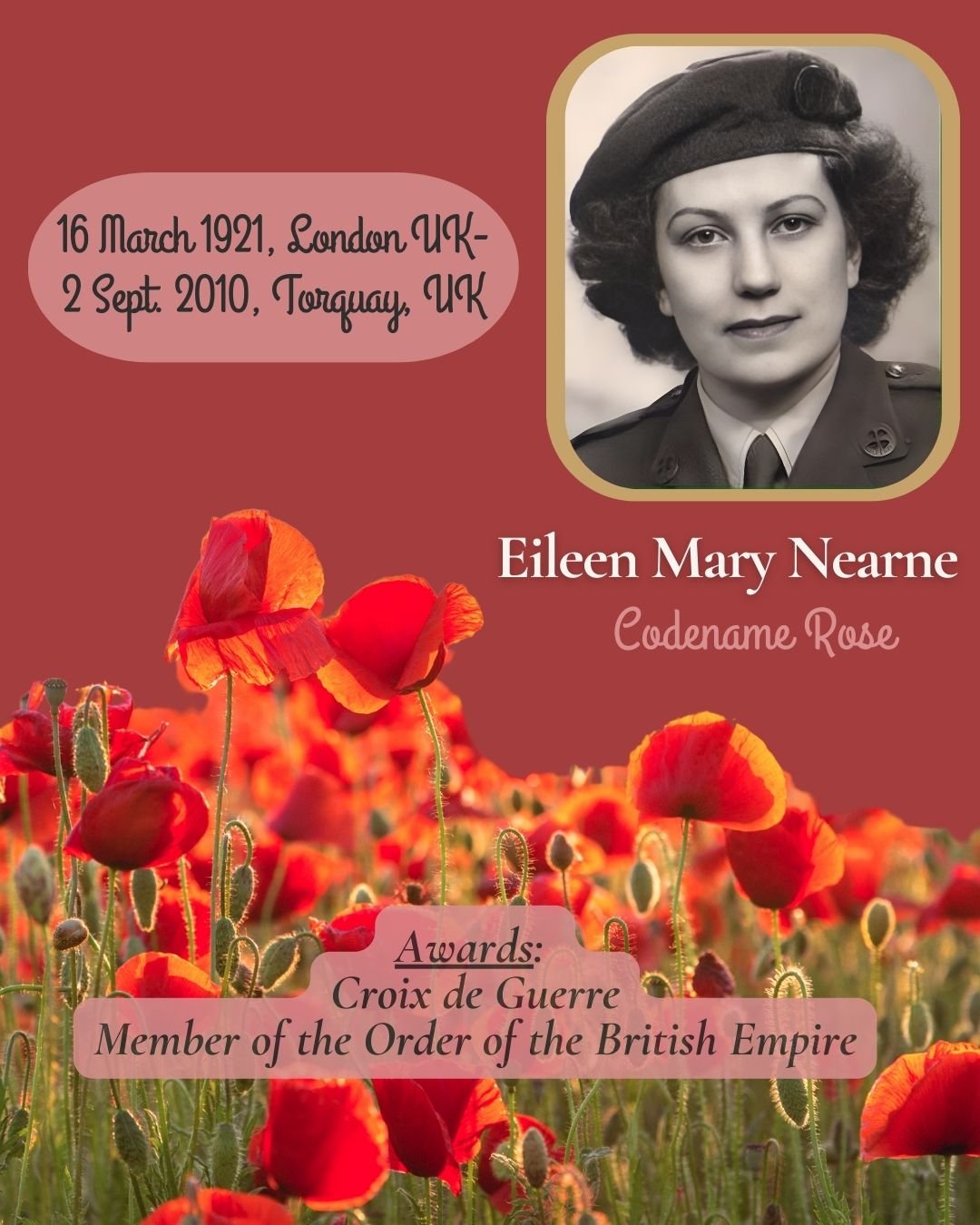

Eileen Nearne: The Unbreakable Spirit Behind Codename "Rose"

Eileen Nearne, born on March 16, 1921, in London, was one of the most resilient female agents of the SOE. After spending much of her childhood in France, she returned to Britain during the war and was soon recruited into the SOE’s clandestine operations. Fluent in French and fiercely determined, she trained as a wireless operator—one of the most dangerous roles an agent could take on.

In March 1944, under the codename Rose, Eileen was parachuted into occupied France to work as a radio operator for the Wizard network. For months, she transmitted critical messages between the French Resistance and London, facilitating supply drops, coordinating sabotage missions, and relaying vital intelligence. Despite the constant threat of detection, she remained steadfast, sending over a hundred transmissions—each one a potential death sentence if intercepted.

Her luck ran out in July 1944 when the Gestapo captured her. Despite brutal interrogation and torture, she refused to break, insisting she was an innocent civilian who knew nothing of espionage. Deported to Ravensbrück concentration camp, she endured forced labor and starvation but never lost her resolve. In early 1945, she escaped during a prison transfer and was eventually liberated by American troops.

After the war, Eileen was honored with the Croix de Guerre by France and appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for her extraordinary bravery. However, she lived out her later years in quiet solitude, her incredible wartime efforts largely unknown to the world until after her passing in 2010.

Her story, though once hidden, stands today as a powerful testament to the unwavering spirit of the SOE women. She was, and will always be, a symbol of resilience, courage, and quiet heroism.

You can read my version of Eileen’s life and mission is the recently released The Echo of Valor, Codename Rose.

Anne-Marie Walters: The Young Courier of the Wheelwright Network

Born on March 16, 1923, in Geneva, Switzerland, Anne-Marie Walters was the daughter of an English father and a French mother. Fluent in both languages, she joined the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) in 1941. In 1943, recognizing her potential, the Special Operations Executive (SOE) recruited her as a field agent. At just 20 years old, she became one of the youngest female agents in the SOE, operating under the codename "Colette."

In January 1944, Anne-Marie was parachuted into southwestern France to serve as a courier for the Wheelwright network, led by George Starr. Her role involved transporting messages, coordinating supply drops, and liaising between resistance groups—a perilous task that required constant movement and discretion. She often traveled by bicycle or train, adopting various disguises to evade German forces. Her missions took her across regions such as Auch, Tarbes, and Montréjeau, where she delivered vital information and resources to support sabotage operations against the occupying forces.

In August 1944, as Allied forces advanced, Anne-Marie and her comrades faced intense combat during the Battle of Castelnau. Despite the dangers, she continued her work until the liberation of the area. For her bravery and contributions, she was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) and awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Médaille de la Reconnaissance Française by the French government.

After the war, Anne-Marie documented her experiences in her memoir, "Moondrop to Gascony," providing a vivid account of her time with the French Resistance. She later settled in France, where she lived until her passing in 1998. Her story stands as a testament to the courage and determination of the young women who risked their lives to fight against oppression.

Vera Leigh: The Overlooked Heroine of the SOE

Born on March 17, 1903, in Leeds, England, Vera Leigh was adopted by an American racehorse trainer and raised in France. She became a successful figure in Parisian haute couture, co-founding the fashion house Rose Valois in 1927. With the onset of World War II and the fall of Paris in 1940, Vera joined the French Resistance, assisting in the escape of Allied servicemen from occupied France. In 1942, she made her way to England and was recruited by the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Operating under the codename "Simone," she was parachuted back into France in May 1943 to serve as a courier for the Donkeyman circuit. Her work involved perilous missions, including delivering messages and coordinating resistance activities. Tragically, she was arrested by the Gestapo in October 1943, endured harsh imprisonment, and was executed at the Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp in July 1944. Despite her extraordinary bravery and sacrifice, Vera Leigh received only the King's Commendation for Brave Conduct posthumously. Her story is a poignant reminder of the many unsung heroes of the SOE whose contributions have not been fully recognized.

Note: Vera Leigh's life and service will be further explored in the upcoming book, "The Gift of Grace: Codename Simone," as part of the Timeless Agents series.

Women of the Resistance: Forgotten and Famous Heroines

This month, in honor of Women's History Month, we shine a light on the famous and forgotten heroines of WWII’s resistance movements—women who fought, spied, sabotaged, and sacrificed. Some became legends, like Violette Szabo, whose bravery inspired books and films. Others, like Muriel Byck, Hannie Schaft, and Wanda Gertz, remain lesser known despite their extraordinary courage. Their stories deserve to be remembered.

Throughout history, countless women have risked everything to resist oppression, fight for freedom, and aid the war effort from the shadows. Some became legends, like Violette Szabo, whose bravery inspired books and films. Others, like Muriel Byck, Hannie Schaft, and Wanda Gertz, remain lesser known despite their extraordinary courage. This month, in honor of Women's History Month, we shine a light on the famous and forgotten heroines of WWII’s resistance movements—women who fought, spied, sabotaged, and sacrificed. Their stories deserve to be remembered. Here are some for Women History month. Join me in the Facebook Reader Group as we uncover the incredible lives of these fearless women.

📜 Remembering Violette Szabo – 80 Years On

On 5 February 1945, Violette Reine Szabo, a courageous SOE agent, was executed at Ravensbrück concentration camp. She was only 23 years old, but her bravery and resilience left a lasting mark on history.

Born to a British mother and a French father, Violette risked everything to fight for France’s freedom. Twice parachuted into occupied France, she carried out vital intelligence work and led resistance efforts with unwavering determination. Despite being captured in June 1944, she endured brutal interrogations without breaking, protecting her comrades to the very end.

On 2 February 2025, a commemoration was held in her honor, marking 80 years since her execution. Her legacy remains alive through books, films, and the continued admiration of those who recognize her sacrifice.

My own book in the Timeless Agents series about Violette, The Heartbeat of Freedom, Codename Louise, will be written in due time.

Read more about Violette’s story in this recent tribute:

📖 Her story of the Month – Violette Szabo

🕯 Lest we forget.

#VioletteSzabo #SOE #WWIIWomen #WomenOfTheResistance

📜 Remembering Muriel Byck – The SOE Agent Who Never Got to See Victory

Muriel Tamara Byck was a young Jewish woman who risked everything for the cause of freedom. Born in France but raised in Britain, she was recruited into the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and parachuted into occupied France in 1944 as a radio operator—a role with one of the highest mortality rates in the Resistance.

Working under constant danger, Muriel transmitted vital intelligence for the French Resistance, helping coordinate sabotage operations. Tragically, she fell ill with meningitis in May 1944 and died in a makeshift hospital, never living to see the Liberation of France.

Despite her sacrifice, Muriel’s story remains little known. This July, her legacy will be honored in my upcoming novel, The Call of Destiny: Codename Violette, which is now available for preorder:

📖 The Call of Destiny – Preorder Here

For more about Muriel and other Jewish heroines of the SOE, visit:

🌍 Daughters of Yael: Jewish Heroines of the SOE

🕯 Gone but not forgotten.

#MurielByck #SOE #WWIIWomen #WomenOfTheResistance #JewishHeroines

📜 Remembering Hannie Schaft – The Girl with the Red Hair

Hannie Schaft was a Dutch resistance fighter who struck fear into the hearts of Nazi occupiers. A university student turned resistance operative, she helped Jewish children escape, sabotaged enemy operations, and executed Nazi collaborators—earning her a place on the Gestapo’s most-wanted list.

In April 1945, just weeks before the Netherlands was liberated, Hannie was captured and executed. Her final words before being shot: “I shoot better than you.” Even in death, she remained defiant.

Having lived in the Netherlands for many years, I’ve always admired her courage and relentless spirit. Her story has stayed with me, and I’m honored to share it here.

For more on Hannie’s overlooked legacy, read this New York Times tribute:

📖 Hannie Schaft – Overlooked No More

🕯 Lest we forget.

#HannieSchaft #DutchResistance #WWIIWomen #WomenOfTheResistance

📜 Honoring Wanda Gertz – The Woman Who Became a Soldier

Wanda Gertz was a Polish patriot whose determination knew no bounds. Born in 1896 in Warsaw, she was inspired by her father's tales of the January Uprising. At a time when women were barred from combat, Wanda cut her hair, donned male attire, and enlisted in the Polish Legion during World War I under the alias Kazimierz "Kazik" Żuchowicz. Her courage and skill led her to serve in various capacities, including commanding an all-female sabotage unit during World War II. Despite facing imprisonment and numerous challenges, her spirit remained unbroken.

For a comprehensive look into her life and legacy, this article offers detailed insights:

📖 Wanda Gertz – The Symbol of Female Courage in World War II

🕯 Remembering a true heroine.

#WandaGertz #PolishResistance #WWIIWomen #WomenOfTheResistance

📜 Honoring Andrée de Jongh – The Architect of the Comet Line

Andrée de Jongh, affectionately known as "Dédée," was a Belgian resistance heroine who, during World War II, established the Comet Line, a clandestine network that rescued Allied airmen shot down over occupied Europe. Born in 1916 in Schaerbeek, Belgium, she was inspired by the bravery of Edith Cavell, a British nurse executed in World War I for aiding soldiers' escapes. Dédée's unwavering courage led her to personally escort numerous airmen across treacherous terrains, including the Pyrenees, guiding them to safety in neutral Spain. Her relentless efforts saved countless lives, and even after being captured and enduring imprisonment in concentration camps, her spirit remained unbroken.

For a comprehensive look into her life and legacy, this article offers detailed insights:

📖 Andrée de Jongh: Faster Than a Comet

🕯 Remembering a true heroine.

#AndréeDeJongh #CometLine #BelgianResistance #WWIIWomen #WomenOfTheResistance

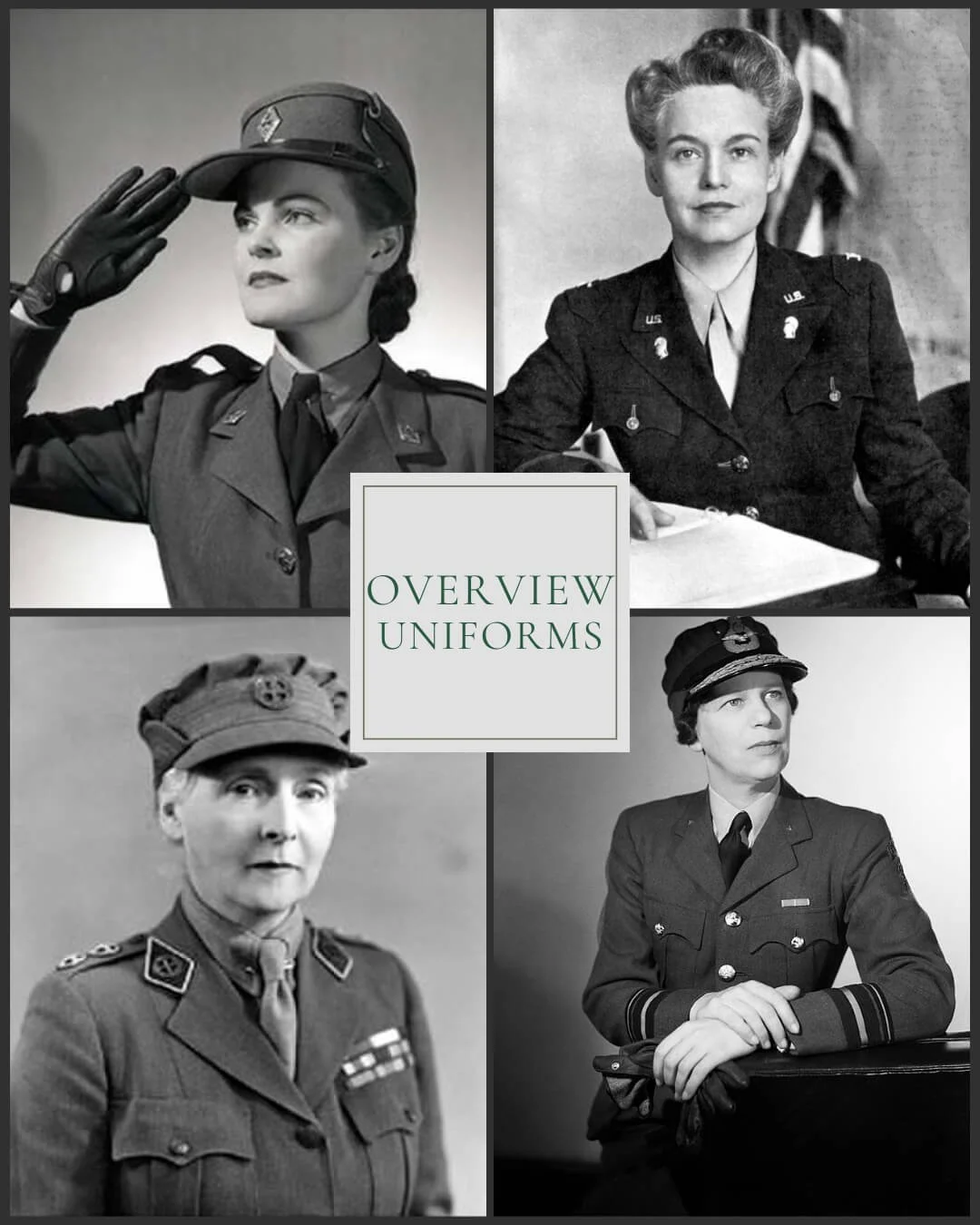

Revolutionary Roles: Women’s Military Uniforms in WWII

World War II marked a turning point in history—not just on the battlefield but in how societies redefined roles for women. For the first time, women donned official military uniforms, stepping into roles that challenged traditional gender norms and showcased their courage, skill, and resilience. Join me as we explore the stories behind these iconic uniforms, the brave women who wore them, and the revolutionary shift they represented in military and social history.

World War II marked a turning point in history—not just on the battlefield but in how societies redefined roles for women. For the first time, women donned official military uniforms, stepping into roles that challenged traditional gender norms and showcased their courage, skill, and resilience. From the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) to the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY), these uniforms symbolized a blend of functionality and groundbreaking progress.

Each of the uniforms featured in this blog post—WAAF, FANY, ATS, CWAC, AWAS, and WAC—represents women’s invaluable contributions to the war effort. While this blog focuses on these specific groups, countless others, including nurses and pilots, also wore uniforms that made history.

It’s important to recognize that this blogpost highlights only a few of the many roles women played in WWII. Their contributions spanned far beyond these groups, with numerous unsung heroines working tirelessly behind the scenes and in active service.

Join me as we explore the stories behind these iconic uniforms, the brave women who wore them, and the revolutionary shift they represented in military and social history.

Click image for larger size

FANY Uniforms: A Story of Service and Secrecy

The First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY) played a crucial role during World War II, with its members serving in communications, intelligence, and field operations. Many women agents, including Lise de Baissac and Eileen Nearne, operated under the guise of being part of the FANY. This "cover" provided a layer of official protection while they carried out their daring missions behind enemy lines. The FANY uniform, distinguished by its practical design and smart tailoring, embodied the resilience and courage of the women who wore it.

While the FANY began as a nursing organization, by WWII, its members took on far more diverse and dangerous roles, from radio operators to drivers in active war zones. The uniform was not just a symbol of their service but also a part of the secrecy that made their contributions possible.

Learn more about the FANY and the women who made history in these uniforms here https://www.fany.org.uk/History

Click image for larger size

WAAF Uniforms: Service in the Skies and Beyond

The Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) was established during World War II, and its uniform symbolized a new era of women's active involvement in the military. Unlike some other organizations, WAAF members were given official ranks, marking their roles as integral and not just voluntary. Women like Muriel Byck and Noor Inayat Khan, both SOE agents, wore the WAAF uniform as a form of protection and cover for their clandestine missions.

The uniform itself was practical yet smartly designed, consisting of a blue-grey jacket, skirt, and cap, reflecting its connection to the Royal Air Force. Women in the WAAF served in a variety of roles, from clerks and drivers to wireless operators and radar mechanics. For agents like Muriel and Noor, the uniform provided a semblance of legitimacy as they carried out dangerous operations behind enemy lines.

While Noor Inayat Khan tragically lost her life in service, her story, alongside Muriel’s, underscores the immense courage and sacrifice of WAAF members who shaped the war effort in both visible and hidden ways.

Dive deeper into the history of the WAAF and the women who served with bravery here https://rafhornchurch.com/history/waaf/

Click image for larger size

ATS Uniforms: Service on the Home Front

The Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), the women’s branch of the British Army during World War II, was a vital part of the military effort. Its uniform, consisting of a khaki jacket, skirt, and cap, mirrored that of their male counterparts while being tailored to women. The ATS uniform symbolized the expanding roles of women, from clerks and cooks to mechanics, drivers, and anti-aircraft gunners.

Among the many women who wore the ATS uniform was Princess Elizabeth, the late-Queen Elizabeth II, who joined the ATS in 1945 as a second subaltern. She trained as a driver and mechanic, becoming the first female member of the royal family to serve in the armed forces. Her service in the ATS not only reflected her dedication but also served as a powerful symbol of solidarity with the people during the war.

The ATS uniform showcased practicality and professionalism, blending the need for functionality with military decorum. For the women who wore it, including Princess Elizabeth, it represented a sense of duty and pride in their contribution to the war effort.

Explore the stories of the ATS and its extraordinary members here https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/war-glamour

Click image for larger size

WAC Uniforms: Pioneering Roles in the U.S. Military

The Women’s Army Corps (WAC), established in 1943, marked a significant shift in the U.S. military, allowing women to serve in non-combat roles with official military status. The WAC uniform, designed with practicality and professionalism in mind, included a tailored olive-drab jacket, skirt, and hat, reflecting the military standards of the time.

One of the most notable figures of the WAC was Oveta Culp Hobby, the Corps’ first director. A trailblazing leader, she guided the WAC through its formative years, ensuring women’s roles were respected and impactful. Under her leadership, WAC members served in over 200 job roles, including clerks, radio operators, mechanics, and cryptographers, freeing up men for combat roles and proving the invaluable contributions of women in the armed forces.

The WAC uniform became a symbol of progress and determination, as women stepped into roles traditionally held by men, breaking barriers and reshaping the perception of women in the military.

Learn more about the Women’s Army Corps and its pioneering members here https://unwritten-record.blogs.archives.gov/2013/06/03/dont-walk-like-a-man-be-the-best-wac-that-you-can-be/

Click image for larger size

CWAC Uniforms: Canadian Women’s Contributions to the War Effort

The Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC) was formed in 1941, allowing women to officially enlist in the Canadian Army for the first time. The CWAC uniform, a smartly tailored khaki jacket and skirt paired with a peaked cap, represented professionalism and pride in service. It was designed to provide women with practicality and a sense of equality within the military.

Among the many women who served in the CWAC, Joan Kennedy stands out as a trailblazer. As one of the first officers in the Corps, she was instrumental in recruiting and organizing women for military roles. Under her leadership, CWAC members served in critical support positions, such as clerks, typists, drivers, and medical aides, enabling male soldiers to focus on combat duties.

The CWAC uniform became a powerful symbol of Canadian women’s vital role in the war effort. These women not only contributed to the Allied victory but also paved the way for future generations of women in the armed forces.

Discover the inspiring stories of the CWAC and the women who shaped history here https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canadian-womens-army-corps

Click image for larger size

AWAS Uniforms: Australian Women Supporting the War Effort

The Australian Women’s Army Service (AWAS), formed in 1941, was the first time Australian women were allowed to serve in the army. The AWAS uniform, featuring a khaki jacket, skirt, and slouch hat, reflected the unique identity of Australian servicewomen. Designed for practicality and function, it became a symbol of their commitment and dedication.

One of the most notable figures in the AWAS was Sybil Irving, its founder and controller. A visionary leader, Irving worked tirelessly to organize and expand the AWAS, ensuring women were prepared and equipped to serve in roles such as clerks, drivers, signal operators, and even anti-aircraft personnel. Under her guidance, the AWAS became a vital part of Australia’s war effort, allowing men to be deployed to combat roles.

The AWAS uniform represented more than just military service; it embodied the pioneering spirit of Australian women who stepped forward to serve their country during its time of need.

Explore the history of the AWAS and the incredible women who wore the uniform here https://vwma.org.au/explore/units/3423

Faceless and Forgotten: The Lost Legacy of Madeleine Lavigne

No known photograph of her exists. No memorial bears her likeness. Yet, Madeleine Lavigne was one of the most extraordinary female agents of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), a woman who risked everything in the fight against Nazi occupation. Born on February 6, 1912, in Lyon, France, she dedicated nearly four years to resistance work—creating false identity documents, aiding Allied airmen, and eventually operating as a wireless operator under the codename Isabelle. Despite her courage, her image has been lost to history.

No known photograph of her exists. No memorial bears her likeness. Yet, Madeleine Lavigne was one of the most extraordinary female agents of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), a woman who risked everything in the fight against Nazi occupation. Born on February 6, 1912, in Lyon, France, she dedicated nearly four years to resistance work—creating false identity documents, aiding Allied airmen, and eventually operating as a wireless operator under the codename Isabelle. Despite her courage, her image has been lost to history.

Lavigne's work began at the Lyon town hall, where she used her position to forge documents for those in danger. By 1943, she had become more deeply involved, acting as a courier and providing shelter for SOE agents like Henri Borosh. When the Gestapo closed in, she was forced to flee to England, where she underwent para-military and wireless training before parachuting back into France in May 1944 to establish the Silversmith network in Reims.

Her mission was critical—she kept vital communication lines open, coordinated supply drops, and ensured that resistance efforts remained strong in the final months of the war. When Reims was liberated in August 1944, she was reunited with her children in Paris. But instead of living to see peace fully restored, she passed away on February 24, 1945, from an embolism, leaving behind a legacy that, without images or widespread recognition, has faded into obscurity.

Though history has erased her face, her courage endures. Madeleine Lavigne was posthumously honored with the King’s Commendation for Brave Conduct and the King’s Medal for Brave Conduct, a testament to her silent yet vital contribution to the war effort. But beyond official records, she remains a ghost of history—one of the many women who fought and died without the world ever truly knowing their names, let alone their faces.

Perhaps that is why remembering Madeleine is so important. Because heroines should not remain faceless. Because their sacrifices should never be forgotten. Wait until you’ll find out how a modern-day Marianne Latour pursues Madeleine’s picture in “The Shadow of Silence, Codename Isabelle”.

New Recipe Book: A Taste of Wartime Cooking

I’m thrilled to announce the release of my new recipe booklet, A Taste of Wartime Cooking: Wartime Recipes for the Modern Kitchen. This collection of 15 recipes is inspired by the incredible resilience and resourcefulness of those who cooked during the Second World War. It’s free to download. Come grab your copy here!

I’m thrilled to announce the release of my new recipe booklet, A Taste of Wartime Cooking: Wartime Recipes for the Modern Kitchen. This collection of 15 recipes is inspired by the incredible resilience and resourcefulness of those who cooked during the Second World War. It’s free to download, and you can grab your copy here: Download the RecipeBook.

Why Wartime Recipes?

During WWII, rationing forced cooks to get creative, making the most of every ingredient while stretching rations to feed their families. Despite these challenges, they managed to create meals that were not only practical but also comforting and delicious. This booklet pays tribute to their ingenuity and the simple but hearty dishes that became staples of the time.

The recipes in this collection range from savory favorites like Cold Meat Pasties and Guernsey Potato Peel Pie to sweet treats like Brown Betty and Wartime Chocolate Layer Cake. Each one is a small piece of history, adapted to be recreated in your own kitchen with modern ingredients.

How This Booklet Came to Be

The idea for this recipe collection began in my Facebook Reader Group, where I shared wartime recipes during our December theme. The response was overwhelming, with so many of you sharing your enthusiasm and even trying out the dishes yourselves. It was clear these recipes resonated, and I wanted to gather them into a single, easy-to-access booklet as a way of continuing the conversation and celebrating this shared love of history and food.

What’s Next?

This is just the beginning! I plan to create a second recipe booklet next December, featuring even more wartime-inspired dishes as we revisit this theme in the Reader group. In the meantime, I’d love to hear your feedback—what recipes did you enjoy most, how did they turn out, and what would you like to see in the next collection?

Get Your Free Copy!

Download your free copy of A Taste of Wartime Cooking: Wartime Recipes for the Modern Kitchen here: https://BookHip.com/WHDKCCX.

Thank you for joining me on this journey into the kitchens of the past. Let’s honor the creativity and resilience of those who came before us while sharing the joy of cooking with loved ones today.

Happy cooking!

Hannah Byron

January’s Brave Souls of the SOE

As we step into 2025, I invite you to join me on a year-long journey to honor the extraordinary women of the Special Operations Executive’s (SOE) Section F. These courageous women risked everything to fight for freedom during World War II, their bravery, resilience, and sacrifices becoming a lasting testament to the human spirit in the face of tyranny. Each month, I’ll commemorate the birthdays of these 39 remarkable agents who served in France, often at great personal cost.

As we step into 2025, I invite you to join me on a year-long journey to honor the extraordinary women of the Special Operations Executive’s (SOE) Section F. These courageous women risked everything to fight for freedom during World War II, their bravery, resilience, and sacrifices becoming a lasting testament to the human spirit in the face of tyranny.

Each month, I’ll commemorate the birthdays of these 39 remarkable agents who served in France, often at great personal cost. By the end of the year, we’ll have remembered them all—each story, each life, each sacrifice.