Historical Facts & Fiction

Blog categories

The Hunger Winter or the Dutch Famine 1944-1945

The Hunger Winter in the Netherlands was the winter at the end of WW2 from 1944 to 1945 with a great scarcity of food and fuel. It led to famine, especially in the cities of the western Netherlands. At least 20,000 people died of starvation and cold.

Two participants in the hunger expeditions during the hunger winter

The Hunger Winter, also known as the Dutch famine of 1944–1945, was a devastating period during World War II when the German-occupied Netherlands experienced a severe scarcity of food and fuel. The famine was most acute in the densely populated western provinces, resulting in widespread hunger and suffering.

The cause of the famine was a German blockade that cut off food and fuel shipments from farm towns to the western Netherlands. As a result, at least 20,000 people died of starvation and cold, with the majority of the victims being elderly men. The situation worsened as the harsh winter of 1944–1945 set in, freezing rivers and canals and further impeding the transport of supplies.

During the Hunger Winter, the adult rations in cities like Amsterdam dropped to dangerously low levels, with people receiving less than 1000 calories a day. The scarcity of food items, including bread, butter, and meat, led to the consumption of unconventional and insufficient substitutes like tulip bulbs and sugar beets. Many people resorted to the black market, trading valuables for food, while others were forced to dismantle furniture and houses to use as fuel for heating.

In the face of such dire circumstances, humanitarian intervention became crucial. The Swedish Red Cross provided "Swedish bread" flour, and humanitarian airlift operations, known as Operations Manna and Chowhound, were conducted by the Royal Air Force, the Royal Canadian Air Force, and the United States Army Air Forces. Additionally, Operation Faust organized a land-based, civilian supply chain to distribute food within the country. These efforts alleviated the immediate emergency, but the famine persisted until the liberation of the Netherlands by the Allies in May 1945.

The Dutch famine of 1944–1945 left a profound legacy on the health of its survivors and future generations. Studies have shown that children born to pregnant women exposed to the famine were more susceptible to various health problems, including diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and microalbuminuria. Moreover, grandchildren of women carrying female babies during the famine also experienced increased health issues, suggesting intergenerational inheritance of the famine's effects.

The famine also played a significant role in the discovery of the cause of coeliac disease. The shortage of wheat during the famine led to improvements in children with coeliac disease, providing crucial evidence to support the hypothesis that wheat intake aggravated the condition.

One notable figure who survived the Hunger Winter was actress Audrey Hepburn, who spent her teenage years in the Netherlands during World War 2. Despite her later fame and success, she suffered lifelong negative medical repercussions from the experience, including anemia, respiratory illnesses, and œdema.

Overall, the Hunger Winter was a tragic and heart-wrenching chapter in Dutch history, highlighting the devastating impact of war and famine on civilian populations and underscoring the importance of humanitarian efforts in times of crisis.

The Hunger Winter and The Crystal Butterfly

Edda the main character in The Crystal Butterfly escapes most of the Hunger Winter because she is interred at Camp Westerbork. But when she returns to Amsterdam after the liberation of the camp she becomes aware of what’s been taking place in her home city Amsterdam and the entire west of the country.

Here’s a snippet of what she hears:

“Sit, Miss,” Corrie said again. “I’ve done my best to prepare you a proper breakfast but it’s easier said than done with no eggs and only a pinch of flour.” Then Edda remembered the hunger winter that had struck the big cities in the west of Holland in the past months. How had Duifje and her children survived? And her parents? Probably fed by the Germans, Edda thought, but strangely without any anger. Despite being captives at Westerbork, at least they had enough food.

As if guessing her train of thought, Corrie said, “You’re lucky you found us here, Miss Edda. We’ve only just returned here, you see. We were on Valkena Estate all winter. Took the sickly Marchioness with us. So, we’ve had plenty of eggs and milk. We haven’t had any shortages. Mrs van Leeuwen is only back here with Mr Sipkema to sell the house. We’re all moving to Friesland for good.”

Edda was aware she gaped at the housekeeper and uttered not very coherently, “Valkena Estate? Mother? Friesland?” Sinking on the chair, she tried to make sense of it all. The Sipkema name rang a bell. Her father’s solicitor. Papa had mentioned him as Edda’s go-to, should she need to talk business. That last strained conversation she had had with her father. Talking about his will.

Malnourished children at the time of the liberation in May 1945

Camp Westerbork: 97,776 Jews deported to German concentration camps

Camp Westerbork was a Nazi transit camp in the province of Drenthe in the Northeastern Netherlands. Transport trains arrived at Westerbork every Tuesday from July 1942 to September 1944; an estimated 97,776 Jews were deported during the period. Anne Frank and her family arrived in Westerbork on 4 August 1944 and the family was put on a transport to Auschwitz on 3 September.

Top left: the bent rail track. Top right: Hauptsturmführer Albert Gemmeker and Frau Hassel’s Green Villa overlooking the camp. Bottom left: the only original barrack. Middle: every deported and killed Jew has a stone with a starBottom Right: the original cattle train that deported the Jews and Sintis/Roma’s with the tour guide.

Camp Westerbork was a Nazi transit camp in the province of Drenthe in the Northeastern Netherlands. Transport trains arrived at Westerbork every Tuesday from July 1942 to September 1944; an estimated 97,776 Jews were deported during the period. Anne Frank and her family arrived in Westerbork on 4 August 1944 and the family was put on a transport to Auschwitz on 3 September.

During World War II, Camp Westerbork, situated in the Northeastern Netherlands, was known as the ominous "gateway to Hell." Originally established in 1939 as a refugee camp for Jews fleeing Nazi persecution in Germany and Austria, its purpose drastically changed when the German forces invaded the Netherlands in 1940. It was then repurposed as a transit camp, used to stage the deportation of Jews to concentration camps like Auschwitz and Sobibor.

Although not designed for industrial murder like extermination camps, Camp Westerbork played a significant role in the Nazi's horrific agenda. The camp covered only half a square kilometer and was considered "humane" by Nazi standards. Jewish inmates with families were housed in interconnected cottages, while single inmates resided in oblong barracks.

Number of Jewish communities in Netherlands before and after WW2

The deportation process involved regular transport trains arriving at Westerbork every Tuesday between July 1942 and September 1944. Around 97,776 Jews were deported during this period, destined for concentration camps where the vast majority faced immediate death upon arrival.

Surprisingly, Camp Westerbork featured various facilities and activities designed to give inmates a false sense of hope and maintain order during transportation. These included a school, orchestra, hairdresser, and restaurants.

Among the notable prisoners at Westerbork were Anne Frank and Etty Hillesum, both of whom documented their experiences in diaries later discovered after the war. Sadly, Anne Frank was deported to Auschwitz from Westerbork and perished there.

The camp's leadership changed over time, with Jacques Schol, a Dutchman, serving as the commander initially. However, in 1942, German authorities took control, and Albert Konrad Gemmeker became responsible for sending thousands of Jews to their deaths.

The camp's dark chapter finally came to an end in September 1944, as transports ceased, and Allied troops approached. The camp was liberated by Canadian forces on April 12, 1945.

In retrospect, Camp Westerbork serves as a haunting reminder of the atrocities committed during the Holocaust, and its story continues to bear witness to the resilience and courage of those who suffered under its oppressive regime.

Camp Westerbork and The Crystal Butterfly

Though Westerbork wasn't per se a camp where Dutch resisters were held, as I say in my video, some of our brave WW2 heroes and heroines were taken there usually to be immediately killed n front of a firing squad somewhere in the province of Drenthe. Edda Van Der Valk ends up in Westerbork in August 1944 together with her neighbour Tante Riet. To read more about Edda’s uncommon treatment by Hauptsturmführer Albert Gemmeker read chapters 39 to 44 of The Crystal Butterfly.

Here’s the snippet where Edda meets Gemmeker for the first time….

She placed the brown leather suitcase, with its reinforced metal corners, on top of the table. Still somewhat weak yet with her legs feeling surprisingly strong, Edda gazed outside, trying to come to terms with her captivity, her aloneness, the mission Doctor Samuels had given her. “Stay alive”. Why had this never seemed a mission before? One breathed in and out, one lived, but getting orders to stay alive, seemed odd, unnatural. And yet there had been an urgency in the old psychiatrist’s voice, as if commissioned by God to deliver this message to her. “Stay alive!”

Edda gasped. She suddenly understood. The epiphany made her sink down on the chair, open-eyed, horrified. She was the witness of a secret, inconceivable, inhumane act of barbarity. Far worse than the occupation, far worse than bombs and casualties of war. Her sixth sense had tried to tell her every day but she hadn’t listened, couldn’t listen. Hitler was massacring all the Jews he could get his hands on. They were not coming back from the East. Not coming back. Ash would not come back. Not come back.

And she? She had to stay alive to bear witness to the times her people were living through. She would testify to the rest of the world what the anti-Semites had done in Holland during the war. Find evidence, bring to justice those who’d systematically extinguished the Jewish race—innocent people, families, husbands, wives, siblings, children, babies, and grandparents.

“Miss Van der Valk?” A German-laced voice said behind her. Edda turned gracefully, as a ballerina would, tears in her eyes but her heart full of confidence in her mission. Before her stood an attractive German high official, whom she immediately recognized as the Camp Commander, Albert Gemmeker, who was better known by his nickname, the ‘Gentleman Crook’.

She’d heard the talk he lived with Frau Hassel, who apparently doubled as his mistress and his secretary in the big green villa overlooking the camp. Opulence starkly contrasting with the hand-to-mouth existence in the barracks.

He stretched out his hand, well-manicured but ringless. Edda hesitated. It was against her principles to shake hands with Nazis, but Doctor Samuel seemed to whisper in her ear, ‘Stay alive!’ so she snapped to attention without words of greeting but with a curt nod.

“I heard you’ve been quite ill, Miss Van der Valk. Was the treatment in our hospital satisfactory?” The tall German with his open face and polite manners looked at her frankly with what seemed a genuine smile of interest on his lips.

You’re an enigma, shot through Edda’s mind, but you’re not who you pretend to be.

“Quite satisfactory, Sir. Doctor Samuels is an excellent doctor.”

“He is,” Gemmeker replied with a sigh. “The great doctor will be sorely missed here but his expertise was needed elsewhere.”

Then why did you let him go? Edda wanted to shout but bit her tongue.

“Anyway, Miss Van der Valk, I came here to personally invite you to dinner with my secretary and me tonight. My housekeeper, Frau Asch, is an excellent cook and Doctor Samuels advised me you had not been eating well before you came here.”

Monument at Camp Westerbork for some of the killed Dutch Resistance fighters

The Bunker Drama in Concentration Camp Vught

The bunker drama was a retaliatory measure on 15 January 1944 against 74 female prisoners in the Nazi concentration camp Vught in the Netherlands. Camp commander Adam Grünewald locked the women up in cell 115 in ‘de Bunker’. The cell had an area of 9 square meters and did not have adequate ventilation. After 14 hours the cell was opened again.

Concentration Camp Vught (Netherlands), which the Germans called “Konzentrationslager Herzogenbusch”, was one of the very few SS concentration camps outside Nazi-Germany during WW2.

Though I could write an entire book about this concentration camp, for this blog I will concentrate on one horrible event that took place there in the night of 15 to 16 January 1944. 74 women - most of whom were resistance fighters - were locked up in a tiny cell. The worst of all was that this was a brand-new cell, and the cement reacted to the women’s perspiration creating horrible burns.

They had no water, no air, no food. Ten, eventually eleven, of the women didn’t survive the ordeal. The rest of them had to live with the mental and physical scars for the rest of their lives.

National Monument Kamp Vught

I visited the Camp for the second time on Thursday (20 July 2023) and made some video footage in and around the cell. I’m still reeling from the visit.

For the rest of this horrible bunker drama, I refer to my new book “The Crystal Butterfly” in which the main character Edda Van der Valk reads about it in the papers. She touches on the incident in her diary. Edda is at that moment in hiding somewhere in The Netherlands after her own act of resistance.

I just read in The Parool (our illegal national newspaper) that a horrible drama involving (mostly) Resistance women took place in Konzentrationslager Herzogenbusch near Vught. Seventy-four female prisoners ‘sanctioned’ another prisoner by throwing water over her, cutting her braids, and taking her mattress. This woman, Agnes Jedzini, had snitched on fellow-prisoners to Camp Commander SS-Hauptsturmführer Adam Grünewald in exchange for an early release. Jedzini reported what the women had done to her to the prison leadership. Horrible retaliatory measures followed. Seventy-four women were locked up in a tiny cell called ‘de Bunker.’ Grünewald himself kicked the door shut. The cell was not even 10 feet by 10 feet, and it did not have any ventilation. After fourteen hours the cell was opened. Ten of the women had died.

I can’t stop thinking about them. I could have been one of them. Instead, I’m relatively safe here, having a lot more food and fresh air than in Amsterdam and great company.

Photo’s taken during fieldtrip to Concentration Camp Vught and the Bunker Drama.

Overview of Camp Vught with the entire camp in detail

The original door to Cell 115 behind which the drama took place

Left, some of the culprits – Right, some of the victims

Notables as hostages: A Nazi attempt to prevent acts of resistance

In May 1942 some 500 Dutch MPs, judges, industrialists, journalists, professors, scientists, writers, company owners and artists were lifted from their beds by the Germans. There was no reason for taking them as prisoners of war as they were not with the resistance. They were imprisoned in Brabant in a former seminary, dubbed Herrengefängnis (Gentlemen prison) to serve as Todeskandidat (death candidate).

Introduction

In May 1942 some 500 Dutch MPs, judges, industrialists, journalists, professors, scientists, writers, company owners and artists were randomly arrested by the Germans and taken hostage.

A hostage-taking by the Nazis of this size and prominence was unique during WW2. And the operation failed lamentably, as the first murder of some hostages only led to infuriation among the Dutch.

From 4 May 1942 until 6 September 1944 this Seminary was misused by the German occupation as a Dutch hostage camp. This memorial stone was placed on 14 August 1948 by the former hostages.

Beginning

Already in 1940, the Nazis captured many prominent Dutch individuals as hostages in response to the capture of Germans in the Dutch East Indies. These hostages, known as the Indian hostages, were initially interned in various locations, for example, in Buchenwald in Germany, before being transferred to Camp Sint-Michielsgestel. The camp housed both the Indian hostages and approximately 460 Dutch prisoners captured in May 1942. The internment of the Indian hostages became unnecessary when Japan conquered the Dutch East Indies, leading to transferring German prisoners to British India.

Camp Sint-Michielsgestel, - dubbed Hitler’s Herrengefängnis (Gentlemen prison) - was located in a seminary in Sint-Michielsgestel. It held prominent Dutch figures as collateral - Todeskandidat (death candidate) - aiming to exert control over the Dutch resistance. Despite being hostages, their treatment was relatively lenient, with freedom within the camp, no assigned work, and access to various activities such as movie nights, concerts, and exhibitions. The camp population was released in September 1944, with some individuals being freed in other locations.

However, there were some horrible reprisal executions carried out by the Germans in response to resistance actions. Several internees, including Robert Baelde and Willem Ruys, were executed on different occasions. The first execution was in retaliation for a failed bomb attack on a German army train in Rotterdam, while the second execution was in response to resistance activities in Overijssel.

On the third anniversary of the murder of five hostages their freed camp mates memorized their executed friends for the first time on the crime scene. 15 August 1945, the hostages of Gestel and Haaren.

Camp Sint-Michielsgestel became a hub of intellectual and social interaction, breaking down the pre-war societal divisions. It provided a platform for discussions and debates among individuals from different backgrounds and ideologies, fostering a sense of unity and political innovation. Notable internees included future politicians like Wim Schermerhorn, Willem Banning, and Jan Eduard de Quay, as well as figures such as Frits Philips, Pieter Geyl, and Marcel Minnaert.

An annual commemoration takes place at the execution site in the Gorp en Roovert estate in Goirle, where a memorial and monument were erected.

A diary fragment from a former hostage

“Fear and Threat

We lived in relative comfort, very different from the people in the concentration camps, where mistreatment and punishment were customary.We had self-government within our hostage community.Everybody made his own daily schedule. There was a cheerful, though uptight spiritual life. Family and friends, but also unknown people, showered us with packages. But we were locked up behind barbed wire.End Death threatened us. Death came in the night and murdered some of us. He kept threatening. He came back and crept through the darkness, aiming beams of light from his lantern at the sleeping ones, who awoke in dismay.That was just to scare us.Death reappeared, summoned a few and then sent them back to life.He did it just to tease us. Then he would strike again.”

The Hostage affair and The Crystal Butterfly

In The Crystal Butterfly Ludovicus Count Van Limburg Stirum is introduced as a middle-aged attorney and distant relative who vies for Edda’s attention. She doesn’t pay much attention to him. Until she hears of his horrible fate…

The Crystal Butterfly is now live. Get your copy now.

The Difficult position of The Jewish Council (De Joodsche Raad)

The Jewish Council was a Jewish organization set up in the Netherlands by order of the German occupiers to govern the Jewish community. In essence, the body became a conduit for anti-Jewish measures. In September 1943, the leadership of the Jewish Council was deported to the Westerbork transit camp, and the council ceased to exist.

Introduction

Of the approximately 160,000 Jews in the Netherlands at the time of WW2, 107,000 were deported and only 5,200 of them returned alive: about 73 percent of them did not survive the Holocaust. With this number, the Dutch Jews suffered the highest number of victims per capita in the Holocaust. One reason for this massacre was wryly enough “De Joodsche Raad” (the Jewish Council).

The Jewish Council was established by order of the Germans in 1941 and was the Jewish organization instructed to ‘manage the Jewish community in the Netherlands during the war’. Through the Council, the occupier issued orders to the Jewish community. As a result, the members of the Jewish Council faced major dilemmas.

The ultimate words to what extent this Council was half-guilty or not of collaboration with the German occupiers will probably never be fully answered.

Gemmeker (Camp commander Westerbork) and Aus der Fünten (Responsible for Deportation Jews) Christmas 1942

The Dilemmas

During the meeting in which the Jewish Council learnt of the occupiers' plans to start deporting Jews to labor camps in Germany, some council members expressed anger and frustration, questioning the Council's role and suggesting resistance to the occupation.

In particular, a meeting between the Jewish Council's chairmen Abraham Asscher and David Cohen and Hauptsturmführer Ferdinand aus der Fünten, who was the informal leader of the German body responsible for carrying out the deportations, the Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung, resulted in much confusion.

The chairmen were shocked by the announcement of imminent deportations, but Aus der Fünten assured them that many Jews would remain in the Netherlands. The Council faced the dilemma of whether to cooperate or refuse. Eventually, they decided to assist in the registration and deportation of Dutch Jews, by registering all the Jews and helping with assembling the deportees in the “Hollandse Schouwburg” and continuing to distribute the German ordinances and threats in Het Joodsche Weekblad, (The Jewish Weekly Newspaper).

Every instance where the Council protested against the deportations was answered by more deceptive and manipulative answers by Aus der Fünten, who constantly spread lies of false hope and concessions.

The deception included the illusion of negotiation and the myth that Jews were being sent to “reasonable” labor camps. The Briefaktion, a scheme involving forced postcards from extermination camps, further perpetuated this deception. Despite rumors of mass murder, the chairmen dismissed them as propaganda and believed the postcards were genuine.

Both Abraham Asscher and David Cohen survived World War II.

Jewish Council leader David Cohen, center, and two members of the council during the deportation of Jews on 20 June 1943

The Crystal Butterfly and The Jewish Council

Edda mentions the “Joodsche Raad” several times, also in her diary. Here’s a snippet where she writes about the distribution of the yellow stars.

Amsterdam, 29 April 1942

The Nazis will never stop. A new humiliation has been announced today and I fear it will break my proud Ash. As of the 3rd of May, all Jews must wear a six-pointed yellow Star of David with the word ‘Jood’ on it.

It’s a preposterous measure. Why would we want to label our fellow citizens on the street as Jews? It will only make them feel further isolated from non-Jewish Dutch. And if they don’t wear the star, they can be sent to a concentration camp!

There will be much confusion, I fear. I haven’t spoken Ash about it yet, but it is the “Joodsche Raad” who must distribute the stars among the Jews in Holland. Three days they’ve been given to hand them out. And the Jews have to pay for these wretched stars themselves. Four stars per person for four cents each. Children as young as 6 years old have to wear them. Apparently, a total of 569,355 Stars of David have to be distributed.

I’m appalled! Herr Hitler, you are mad!

Registration of arrested Jews in the Hollandsche Schouwburg

Registration of arrested Jews in the Hollandsche Schouwburg on the Plantage Middenlaan

After the first transports in the summer of 1942, fewer and fewer people responded to the German call to report for departure to Westerbork. The Amsterdam police picked up the Jews from home and brought them to the Hollandsche Schouwburg. The Joodsche Raad had made a number of provisions in the theater, but these were by no means sufficient to reasonably accommodate three to four hundred people. Sometimes the detainees only stayed there for a day, but the stay could also take a week. In the dark of the night the Jews left for Westerbork.

The Joodsche Newspaper 7 August 1942

The Jewish Newspaper

(under the authority of the Jewish Council)

The German authorities announce:

1. All Jews who do not immediately comply with a call to them for labor expansion in Germany, will be captured and sent to the concentration camp at Mauthausen.

This or other punishment will not be applied to those Jews, who still, with hindsight, decide to appear before Sunday, August 9, 1942, at 5 o'clock, report or declare that they are prepared to participate in job creation.

2. All Jews who do not wear the Star of David shall be sent to the concentration camp at Mauthausen.

3. All Jews who change their place of residence or residence without the permission of the authorities - even if they do so only temporarily - are sent to the Mauthausen concentration camp.

The new Holocaust Names monument of Amsterdam

The new Holocaust Names monument of Amsterdam and its characteristic red walls, built with thousands of red bricks. Above you see the large mirrors. Each red brick has an inscription of one name of the thousands of Jewish victims during the Second World War; free photo Amsterdam by Fons Heijnsbroek, April 2022

The February Strike: The Common Man Against Nazi Occupation

The February strike was a strike on 25 and 26 February starting in Amsterdam and spreading out over the Netherlands. It was the first and only large-scale resistance action against the German occupiers and an open protest against the persecution of the Jews, unique in occupied Europe.

Introduction

On February 25, 1941, tens of thousands of Amsterdammers stopped work and took to the streets to demonstrate against the German occupiers.

The February strike was a reaction to the increasingly harsh measures being taken against the Jews. Not only by the Germans but also by the Dutch NSB. The WA, uniformed troops of the NSB, provoked the Jewish neighborhoods (“Jodenbuurt”), smashed windows and forced cafe owners to put up placards saying, “Jews not wanted”. There were fights almost every day.

Ordinary brave strikers

Background

On 9 February 1941, mass fights broke out on the Rembrandtsplein near the Jewish quarter. Jewish boys clashed with the WA. On 11 February, NSB member Hendrik Koot was wounded during a fight and died later. On 19 February, a patrol of the German Ordnungspolizei was ambushed in IJssalon Koco.

Hanns Rauter, the German chief of the SS and police in the Netherlands, reported the incidents to SS leader Heinrich Himmler and expanded the facts considerably. Himmler, Rauter and Reichskommissar Arthur Seyss-Inquart decided on a tough approach; the first raid took place on 22 and 23 February. To set an example, a total of 427 Jewish men aged between twenty and thirty-five were deported to camp Schoorl.

Typewriter with strike leaflet

The Strike

The ‘Jew hunt’ led to fierce outrage among the Amsterdammers. On February 24, municipal workers gathered at the Noordermarkt for a meeting of the underground Communist Party of the Netherlands (CPN) and decided to go on strike. Workers from various companies were also called to strike through a manifesto that was distributed in the early morning.

Strikers succeeded in blocking trams as they tried to leave the depot. Due to the absence of the trams, everyone noticed that there was a strike and more and more people joined what would become one of the greatest acts of resistance against Nazi Germany. Businesses closed their doors and students left their classrooms. The strike spread. A day later, people in Hilversum, Haarlem, Utrecht and other places also stopped working.

The Germans intervened with harsh measures to end the strike. Nine people were killed, 24 seriously injured and numerous strikers were arrested. After two days the strike was over – also under pressure from the Amsterdam city council. The participating cities were fined heavily by the Germans. Amsterdam had to pay 15 million. After the strike, the hunt was opened on members of the Communist Party. Another planned strike was cancelled because of this.

Jewish Amsterdammers held at gunpoint

Historical value

The February strike is a unique event in the history of the occupation; it is the first public protest against the Nazis in occupied Europe and the only mass protest against the deportation of Jews to be organized by non-Jews.

It was also the last public expression of dissatisfaction with the fate of the Jews; the occupier had suppressed the strike with such violence, most Dutch people opted for passivity, while a smaller group set up underground organizations (see blogpost Resistance movement) to protect their Jewish fellow citizens against the Nazis.

Passport photos strikers

Commemoration

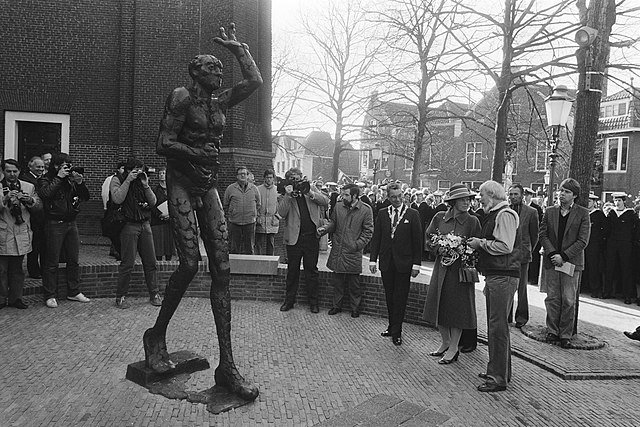

The February Strike is commemorated annually at the statue “De Dokwerker” on Jonas Meijerplein in Amsterdam. The bronze sculpture of a striking dock worker, made in 1952 by sculptor Mari Andriessen, symbolizes the resistance of the common man against the occupier.

Dokwerker Statue Amsterdam

The February Strike and The Crystal Butterfly

In my soon-to-be released 6th novel in The Resistance Girl Series, The Crystal Butterfly, main character Edda Van der Valk keeps a diary to register all the Germans are doing to her country. This is what Edda writes in her diary after the February strike.

Amsterdam, 27 February 1941

We’ve had two extraordinary days! But also very sad ones. I never thought it possible, but the Dutch actually stood up to the Germans in a two-day national strike. It started here in Amsterdam, but it also spread to other parts of Holland. I fear it will backfire on us but at least it gave those who hate the Nazis a boost. I also now know for sure my neighbor Mevrouw Meulenbelt is anti-German, as we finally talked.

(…)

The strike was immediately knocked down by the Germans and I fear harsh repercussions. I truly hope they won’t take it out on poor Van Limburg Stirum and the other hostages!

However, the spree of freedom was exhilarating. I just wish I had the courage to really show which side I’m on. Well, I don’t. But I can tell you, Herr Hitler and your mouthpiece Meneer Mussert, we won’t lay down without another fight. So be prepared.

Het Oranjehotel: from Nazi prison to National monument

The Oranjehotel was the nickname for the Scheveningen prison during WW2. More than 25,000 people were imprisoned here between 1940 and 1945 for interrogation and trial. Arrested for actions that the German occupier saw as a violation. Resistance fighters, but also Jews, communists, Jehovah's Witnesses and black marketers. The prison was already called the ‘Oranjehotel’ during the war. An ode to the resistance fighters who were imprisoned here.

“In this prison / there is no scum / but Dutch glory / damn it!”

Introduction

Het Oranjehotel was the prison established by the Nazis in Scheveningen, Netherlands during World War II. Over 25,000 people were detained in this prison, including members of the Dutch Resistance, Jews, Jehovah's Witnesses, and individuals accused of economic offenses. The name “Oranjehotel” was given by the Dutch as a tribute to the imprisoned Resistance members, while the Germans called it “Polizeigefängnis”.

Doodenboek (Death Book)

The prisoners

Under extremely harsh conditions, the prison housed Dutch people from various backgrounds, including soldiers, students, artists, politicians, and clergy. Political prisoners and those arrested based on ethnicity, philosophy of life, or sexual orientation were also held there. Specific resistance groups were imprisoned here, such as De Geuzen (see last week’s blogpost), as well as secret agents betrayed in the German’s Englandspiel. There were numerous instances of torture and death of prisoners. Many of the detainees were sentenced to long stays in German camps or prisons, and more than 250 people were executed on the nearby Waalsdorpervlakte.

Doodencel 601 (Death Cell 601)

After the war

After the war, the prison briefly served as a detention center for collaborators and members of the Nazi regime. In 1947, the Oranjehotel Committee was established to create a lasting memorial at the prison site. The Oranjehotel Monument, including "Doodencel 601" (Death Cell 601) and commemorative plaques, was created.

The Oranjehotel Foundation was formed to manage the monument and organize annual commemorations. In recent years, efforts have been made to preserve and renovate the prison as an authentic monument.

Cell 601 (see video) was a death cell where inmates waited before being taken to the execution site. The cell has been preserved in its original state and contains inscriptions by prisoners. Several well-known individuals, such as Bernardus IJzerdraat (Geuzen leader), Erik Hazelhoff Roelfzema (Soldier of Orange) and Corrie ten Boom (Christian hider of Jews) and George Maduro (Madurodam was dedicated to him), were imprisoned in the Oranjehotel.

The prison complex remained in use until 2009 and was opened as a Commemorative Center in 2019. Visitors to the Oranjehotel National Monument can learn about the stories of the prisoners and experience the conditions they endured. The permanent exhibition emphasizes the importance of remembering the sacrifices made during times of injustice, oppression, and persecution.

National Monument Oranjehotel

The Crystal Butterfly and Het Oranjehotel

The Oranjehotel is mentioned twice in The Crystal Butterfly and the last time is the most important one. Edda visits the prison after the war when her father is detained there as a member of the National Socialist movement.

A snippet:

She was the only visitor with her father in a large room with small tables each with two chairs. Guards stood at the two entrance doors, listening to every word they would exchange and ready to grab the prisoner by the arms should he so much as utter a favorable word about the NSB.

Edda fumbled with the button on her jacket, racking her brain what to say. Her father stared at the Formica table. He sat very still, hunched and withdrawn into himself. Edda knew she would have to open the conversation.

“How are you, Father?”

“Good.”

Better be honest. “You don’t look like you’re ‘good’, Father.”

She saw him shift slightly in his chair.

“What do you expect me to say then, Eddaline?”

“You could perhaps start with asking me why I am here?” she said it as lightly as possible.

“There was no need to come. I left everything in your name.” A toneless, dead voice.

“That’s not what I mean, Father. I needn’t have come here to find that out. Duifje and Jan Sipkema already told me.”

Later Edda thought it must have been the mentioning of his solicitor that made the change. Her father looked up and Edda almost jumped back in her chair. His eyes, her father’s eyes, once merry and blue like Duifje’s, were colorless, lifeless, disinterested. His soul was dead. What had happened to her formidable Papa? And that was what she blurted out.

“Papa, what has happened to you?”

“What do you mean? I was arrested. As I should have been. So, all’s well.”

National Monument Oranjehotel

The First Dutch Resistance Movement in WW2: The Geuzen

During WW2, most Dutch citizens tried to maintain normalcy under German control, but some resisted. Bernardus IJzerdraat formed the Geuzenactie resistance group, but their lack of secrecy led to their arrest and execution. Despite this, their bravery was honored after the war through memorials and organizations dedicated to promoting democracy.

Introduction

After the surrender in May 1940, most Dutch citizens aimed to maintain their normal way of life amidst German control. This involved cooperating with the occupiers to prevent increased interference in the government and economy. While the authorities initially urged the population to obey and avoid resistance, some individuals immediately opposed the German occupiers. On 14 May 1940, the first Dutch resistance group, ‘De Geuzen’ (The Beggars), was established in Vlaardingen.

Leader of The Geuzen, Bernardus IJzerdraat

Foundation and actions

One of the people to immediately turn away from the German occupier was Bernardus IJzerdraat. IJzerdraat was a resident of Rotterdam and worked as a teacher in the vicinity of Rotterdam. The results of the 14 May 1940 bombing of Rotterdam made such a profound impression on him that he decided to resist. He foresaw “a new Alva soon, with blood council and inquisition”. In line with this comparison with the Eighty Years' War, he named his resistance 'Geuzenactie' (Beggars' action).

IJzerdraat aimed to form a Geuzen army by spreading his message through chain letters. Although his initial message was lost, subsequent messages informed the readers about the occupation’s impact and predicted further restrictions. Jan Kijne, an ally of IJzerdraat, joined forces to sabotage German activities and gather information to pass on to England, where the Dutch government had fled to. They enlisted the help of Ary Kop and formed resistance armies in various cities such as Rotterdam, Maassluis, Delft, Zwijndrecht, and Dordrecht.

The Geuzen primarily focused on sabotage and gathering intelligence, including information about German troops, headquarters, and ships in the Port of Rotterdam. They also compiled lists of NSB members (Dutch Nazi collaborators) and “moffenmeiden” (Dutch girls involved with Germans). While their initial acts of sabotage were on a small scale, the Geuzen hoped to expand their resistance group through chain letters.

Visiting Bernardus IJzerdraat's grave at Ereveld Loenen Netherlands

Betrayal

Fate soon caught up with the Geuzen when Daan van Striep, a young man from Arnhem, obtained an issue of ‘De Geus van 1940’ in November 1940. He shared this with his colleague Johannes Smit, who reported it to the Germans. Van Striep and Smit were both arrested, and Smit revealed information during interrogations.

The Germans quickly arrested other Geuzen members due to their lack of secrecy and inability to warn each other. Ary Kop’s home was searched, resulting in his arrest along with his wife. The Geuzen were imprisoned in Vlaardingen and later transferred to the ‘Oranjehotel’ in Scheveningen (see next blog), where they were interrogated and tortured. Jacobus Boezeman, a Geus from Maassluis, died from torture injuries. Ary Kop was also tortured but managed to communicate with his wife through secret notes.

Trial and Execution

The trial against the Geuzen began on 24 February 1941. During this time, an additional 42 arrests took place, and Abraham Fernandes, a Surinamese Jew, died from torture in prison. 18 members, including IJzerdraat and Kop, were sentenced to death. On 13 March 1941, they were executed by firing squad at the Waalsdorpervlakte, close to The Hague.

It was the first mass execution in the Netherlands. The fusilladed men were buried at the Waalsdorpervlakte by the occupier. It is known that the 18 resistance fighters sang Psalm 43:4 while standing before the firing squad.

“Then I will go to the altar of God,

To God my exceeding joy;

And on the harp I will praise You

O God, my God.”

Another 157 Geuzen were held captive in the Oranjehotel, and many were later sent to concentration camps. Only a few survived the imprisonment.

Bernardus IJzerdraat’s grave at Ereveld Loenen

The Song of the 18 Dead

As a result of the executions, resistance fighter Jan Campert wrote ‘het lied der achttien dooden’ (‘the song of the eighteen dead’). The song of seven stanzas appeared in 1943, when it was illegally published. Campert had then already died in the Neuengamme concentration camp. He was arrested for helping Jewish refugees. The first stanza of 'het lied der achttien dooden' goes:

A cell two metres long for me

But not two metres wide,

That plot of earth will smaller be

Whose whereabouts they hide;

But there unknown my rest I’ll take,

My comrades with me slain,

Eighteen strong men saw morning break -

We’ll see no dawn again.

Posthumously

After the war, the graves at the Waalsdorpervlakte were opened, and the remains were reburied with honor. Several Geuzen members were buried in different locations across the Netherlands. Memorials, monuments, and ceremonies were established in remembrance of the Geuzen and their resistance efforts. The Stichting Geuzenverzet (Beggars’ Resistance Foundation) was founded to preserve and promote democracy and honor those who fought against dictatorship, discrimination, and racism.

Geuzenverzet monument and memorial stone

The Geuzen Resistance and The Crystal Butterfly

Like IJzerdraat, the heroine of The Crystal Butterfly, Edda Van der Valk, is also profoundly shaken by the bombing of Rotterdam and starts her war diaries. She finds the Geuzen pamphlets in her letterbox because her neighbor “Tante Riet” has a nephew in the resistance group. This way Edda follows them from the start and is horrified when she hears of their executions. This is what she writes in her diary. For privacy reasons I’ve changed IJzerdraat’s first name.

13 March 1941

Hendrik IJzerdraat is dead. Murdered by the ironfisted Germans. Together with fifteen other Geuzen. And three men involved in the February Strike. The eighteen men were taken from the Oranje Hotel to the Waasdorpervlakte and shot at point blank in the dunes.

Why? For Heaven’s sake, why?

What did these men do other than forewarn us against the Nazi occupation? They told the Dutch to mistrust Hitler’s ideology and paid for that warning with their lives. It is blatantly clear what the Germans want. Every Dutch inhabitant must dance to their tunes or can get the bullet.

The Geuzen never even touched so much as the sleeve of one German. Oh, the Dutch are enraged. But the pressure is on. The Germans must have believed the Dutch to be much more pliable. Well, we arent’t. But, oh dear God, I fear for what’s next. Neither side will go down without a fight and the Germans have the weapons, the power, and the infrastructure to squash us completely. And they’re getting anxious. The war in North Africa doesn’t seem to go well for them.

I will just write down what I can glean from the papers. It makes me feel more like a correspondent than a resistance fighter. I would never have the guts to openly resist. And with my family rubbing up against Hitler and Mussert, it would be idiocy on my behalf.

But still! Herr Hitler and Meneer Mussert, I’ll do my part. I swear by my Queen and country that I will not lie down and die for you if I can help it.

Geuzen Monument Market Vlaardingen

“Resistance against the enemy always takes place at the right time”

The bronze sculpture depicts a human figure, walking with determination, doubt, and trepidation, knowing his mission is to carry this message to the future. One hand raised in warning, while the other fisted hand protects his own body as he defends himself against the enemy.

At a short distance two severed feet symbolizing life that was ended abruptly.

Rotterdam: From Bombed-out to Best Travel City

The 15-minute bombing of Rotterdam led to the capitulation of the Netherlands. Hitler broke the valiant fight the small Dutch army had put up. Rotterdam’s historic centre was flattened, but the city became a modern architectural marvel after the war.

Introduction

In my soon-to-be released 6th novel in The Resistance Girl Series, The Crystal Butterfly, main character Edda Van der Valk is in Amsterdam when she hears on the radio about the bombing of nearby Rotterdam. Though Amsterdam is also suffering from intruding Germans both on the ground and in the air, the invasion of the Germans and the destruction of Rotterdam is a turning point in Edda. Abhorred, she starts a diary to register all the Germans are doing to her country. The seed of resistance is sown in her.

Amsterdam, 14 May 1940

I don’t know who will win this war, the Dutch, or the Germans, but I do not believe in the right of one country to attack another. It’s not that I’m against Germany. I have German blood myself, but I believe Holland should stay a sovereign country.

As I write this, I’m surprised at myself. I never take sides, not in a political sense, so why do I strongly feel sending bombers and dropping bombs on civilians is the worst way to create stability? Well, the answer is obvious from the question. A child could answer it.

So, Herr Hitler, you are terribly wrong, but I fear it will take a long time before either the world or you yourself will reach a full understanding of your blunder.

I will hide this diary carefully because I’m going to give Herr Hitler a piece of my thoughts every day. Not that he will ever listen to me, but maybe the world will one day.

Marchioness Edda Van der Valk.

Why was Rotterdam bombed?

Rotterdam was bombed by German bombers on 14 May 1940, and 711 people died. About 80,000 residents became homeless. The bombardment was the retaliation of the German invaders for the fights the Dutch troops put up, which had slowed down the German advance. The Netherlands surrendered to the Germans on 15 May 1940.

On the first day of World War 2 in the Netherlands, German paratroopers landed in the south of Rotterdam. However, the marines and units of the Army stationed in Rotterdam held their ground at the Maas bridges. The German war in the Netherlands turned out to be proceeding unexpectedly slowly. Hitler ordered Kampfgeschwader 54 to be deployed in the Netherlands to break the resistance in Rotterdam by all means.

The missed ultimatum

General Schmidt sent an ultimatum to Colonel Scharroo and to Mayor Oud, but Scharroo thought it was way too vague and did not intend to capitulate. Mayor Oud had difficulty connecting with General Winkelman and showed that the national interest came before the interest of the city.

Winkelman bought time by making Scharroo's argument about 'this scrap of paper' his own. A new and more official ultimatum was handed to Von Choltitz fifteen minutes before it expired.

General Schmidt ordered the planned 1:00pm artillery bombardment to be postponed but didn't receive the message that Kampfgeschwader 54 had taken off, so didn't take measures to have the red flares fired. He wanted Scharroo's surrender before 4:20 pm.

The Attack

Within minutes German Heinkel He 111 bombers appeared over Rotterdam. One squadron turned around after seeing red flares fired from Noordeiland directly ahead and dropped their bomb loads on areas below the flight path back to the departure bases, a common procedure to avoid explosion risks on landing.

Rotterdam's historic city centre was destroyed by 97,000 kilos of German high-explosive bombs in the year that it would celebrate its 600th anniversary. After the bombardment, Captain Bakker got through the centre to Colonel Scharroo's headquarters in Blijdorp and capitulated Rotterdam. Commander Wilson left for The Hague to request approval from General Winkelman.

Scharroo reported to the German lines half an hour before the end of the second ultimatum, at 15:50. He signed with 'angenommen', but the German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring ordered a second bombardment between 7:00 and 8:00pm.

General Kurt Student was hit by a beam after a stray projectile hit the command post. Dutch civilians were placed against the wall for a mass execution, but Von Choltitz prevented this mass murder.

The rain of bombs on Rotterdam was enormous, destroying 24,000 homes, 32 churches and 2 synagogues. 650-900 people died and 80,000 people became homeless.

Rotterdam's entire centre was a smouldering mess after the bombing, but several important buildings were spared. The rubble was cleared, and part of it was dumped in the water bodies of the Blaak and the Schie, as well as around and partly in the Kralingse Plas.

Rebuilding Rotterdam

Already in 1940 plans were made for the reconstruction of the city. The old Willemsbrug was also destroyed but was repaired quickly.

Without a historic heart, Rotterdam has a completely different cityscape than other Dutch cities, but today its heart is a thriving multi-cultural and artistic centre. Enough for Lonely Planet to call it Best Travel City in 2016.

Rotterdam 1940

Rotterdam today

WW2 Field Research to "Mussert's Wall" Netherlands

I invite you to join me on my field trip to Mussert’s Wall. Anton Mussert was the leader of the NSB. Learn more about World War 2 in Holland, about the Dutch NSB Party and Collaboration during WW2.

Unveiling the Dark Pages of History: The Dutch NSB Party and Collaboration during World War 2 in Holland.

In an upcoming blog I will shed light on the rise of De Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging, the National Socialist Movement (NSB), in the Netherlands before and during World War 2 and its collaboration with Hitler’s Germany.

The most controversial part of writing The Crystal Butterfly for me was Edda’s parents’ membership of the NSB and their support of Hitler’s ideology. I strongly felt, though–when writing a book on Holland in WW2–collaboration needed to be addressed. Most Dutch people remained neutral during the war, a small yet active part resisted and quite a significant number actively collaborated with the Nazis, whether or not they were a member of the NSB.

I went on a field trip to Mussert’s Wall. Anton Mussert was the leader of the NSB. I invite you to join me on my field trip using the video below.

In 2018 after a lot of debate it was decided that this wall shouldn’t be taken down, as it is an important remembrance for people what happened here. On my photograph you can see what it looks like today and compare it to when it was used over 80 years ago.

Mussert's Wall in 1940

Mussert's Wall in 2023

Feel free to comment below. Share your thoughts, knowledge, experiences. All appreciated!

And stay tuned for more research on WW2 in the Netherlands.

2023: the birth of a new book

New book, but also a new home and a new website. Years of research on European countries during World Wars NOT lost, and more to come! Did you know about Audrey Hepburn’s Dutch war years?

Since book 5 in The Resistance Girl Series, The Highland Raven, came out, I took a short break from writing about my main topic World War 2. In the interim I launched a new historical detective series, titled The Mrs Imogene Lynch Series. I also moved to another part of Holland at the end of December ‘22 and became a first-time grandmother in January. All very exciting but very distracting from my WW2 writing schedule! :-)

In January 2023 I began writing The Crystal Butterfly, my newest book in The Resistance Girl Series. This book is about the Dutch Resistance. It was a Godsent to be able this time to do all my groundwork ‘around the corner’ and I’ll share plenty of my (on the spot) research with you on this blog.

I took the time to deep-dive into the new story and get to the heart of my heroine’s journey before and during WW2. Her name is Edda Van der Valk and in The Crystal Butterfly she will take you through her Dutch war years.

As I now live close to Den Bosch - which is in the centre of Holland - I can easily travel to the most important places of action during WW2 in this country. So let me take you with me on my field trips as I retrace my steps to that gruesome part of our history, now some 80 years ago.

Few people living through WW2 are still with us today. The medalled-up veterans and bravely surviving Jews have become sparse centenaries, whose live presence in TV shows and newspaper articles are almost non-existent. WW2 is now almost history, lived through by the generation of our parents, grandparents, great-grandparents. But I still feel it is my duty to keep the history alive LEST WE FORGET.

The Crystal Butterfly is also inspired by - though far from identical to - Audrey Hepburn’s Dutch war years, so I’ll take you to places where she lived and spent some of the most arduous years of her life. And, of course, Anne Frank cannot be ignored in a book that is centred heavily on the deportations of Dutch-based Jewish people. After all, the arrest of Edda’s big love, Asher Hoffmann, was her reason for joining the Resistance.

PS For avid readers of my blog you may notice I have a new website and miss the abundant archive of years of research on many European countries during the World Wars. Fear not for it will return in an even clearer and more user friendly way.

Hello Reader

Welcome to Historical Facts & Fiction. Here imagination meets reality. I created this blog as a space to assemble my own research that had no place in my World War novels. Find out more about the background to The Resistance Girl Series!

Welcome to Historical Facts & Fiction. Here imagination meets reality. I created this blog as a space to assemble my own research that had no place in my World War novels. I hope you’ll enjoy finding out more about the background to The Resistance Girl Series.

Titbits of research certainly have their place in historical fiction, but when it becomes info dump, it’s too much. But in a blog there’s enough space to share all in-depth investigations and fieldwork to my heart’s content.

Most Historical Fiction readers are fervent researchers themselves; half the fun of reading a good HF novel is popping onto the net to fact-check what you’ve just read. You simply must know if SOE really had women spies, or if Eva Braun actually married Hitler hours before joining him in death. The internet is our treasure trove. I know I can’t stop myself, and love learning a thing or two in the process.

Have you ever wondered where HF authors get their ideas for a new book or series, or how they do their research? No two HF authors are alike – of course – but we all do rely heavily on today’s search engines. No work gets done without it.

However, as you’ll read in an upcoming blog post, my reason for starting The Resistance Girl Series was a family photo I found by chance. Curiosity is a good start. As a European with lineage in several countries, I not only study the lives of these people. They are in my bloodline.

My Great-uncles William and Jack Westcott

But it wasn’t just my uncles’ photograph that incited me to write In Picardy’s Fields. It may sound terrible to say - and I won’t do so aloud - but I love the World Wars. For me as a fiction writer these intense and dark periods in recent human history provide the greatest canvas on which to splash my stories, in an endless variety; this was the period – par excellence – in which ordinary people performed extraordinary deeds. And we all love us a decent hero(ine)!

I’m never tired of learning more about the first half of the 20th century and how it’s shaped our current society. So, please permit me to infect you with some of that passion.

Next to online studies, you can also join me on my field trips to various countries while I do my onsite research.

On to the first blog now…

Thank you for being here!